Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical doctors in Turkey

Main Article Content

We explored the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical doctors working in hospitals assigned to treat COVID-19 patients. An exploratory, descriptive, qualitative research design was applied with a group of 204 medical doctors working within 40 different hospitals across 15 provinces of Turkey. Results reveal that medical doctors experienced various psychological problems, such as personal stress, anxiety, fear, panic attacks, depressive tendencies, and sleep disturbances, during the pandemic period. To cope with the pandemic, the medical doctors exhibited behaviors such as religious prayer, using antidepressants, undertaking different hobbies, paying attention to social distancing and hygiene rules and guidelines, and having a balanced and healthy diet. Our findings demonstrate that COVID-19 increased medical doctors’ psychological pressure and associated physical symptoms.

A novel coronavirus, described as a potentially fatal respiratory infection, was named by the World Health Organization as COVID-19 on February 11, 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020a; Zhu et al., 2020). Since COVID-19 was first identified in late 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, it has spread worldwide to become a pandemic, presenting a clear and immediate global public health threat (Hui et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020b). The pandemic has had a global influence, having negatively affected millions of people’s lives as well as causing significant social, physical, and economic damage and loss. Further, the swift spread of COVID-19 has had a deep effect on the psychology of people and their daily lives, including bringing about significant frustration and causing numerous difficulties that many had not previously experienced.

The first case of COVID-19 in Turkey was confirmed on March 11, 2020 by the Turkish Ministry of Health (2020a). As of the end of August 2020, Turkey had 270,133 confirmed cases, with 244,926 people having recovered and been discharged from hospital, 961 under critical observation, and 6,370 fatalities (Turkish Ministry of Health, 2020b).

According to Fava et al. (2019), health workers are frontline responders whose role includes fighting the COVID-19 pandemic and treating those who have become infected; hence, they face not only an abnormally intense workload, but also the credible risk of becoming infected with the disease at any time while carrying out their job. When considered from this perspective, health workers bear the burden of performing the primary tactical duty in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, by putting themselves and their health in danger, they work selflessly in an intensive struggle against the pandemic. The Turkish Medical Association (2020) reported that many frontline medical professionals have become infected with COVID-19, and that some have also lost their lives owing to the disease. This situation has resulted in serious negative psychological and physical effects on health workers fighting the pandemic.

We aimed to identify the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical doctors who were working in education and research hospitals affiliated with the Ministry of Health in Turkey, by conducting a detailed analysis of their perceptions, feelings, and thoughts. There have been some studies examining the effects of COVID-19 on healthcare workers in Turkey; however, no previous researchers have focused on medical doctors working in the group of hospitals we focused on, and who are directly fighting the COVID-19 epidemic. Our research questions were as follows:

Research Question 1: How do medical doctors describe the effects of dealing with COVID-19 on their psychological well-being?

Research Question 2: What strategies have medical doctors developed to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic in their work life and personal life?

Method

Study Design and Participants

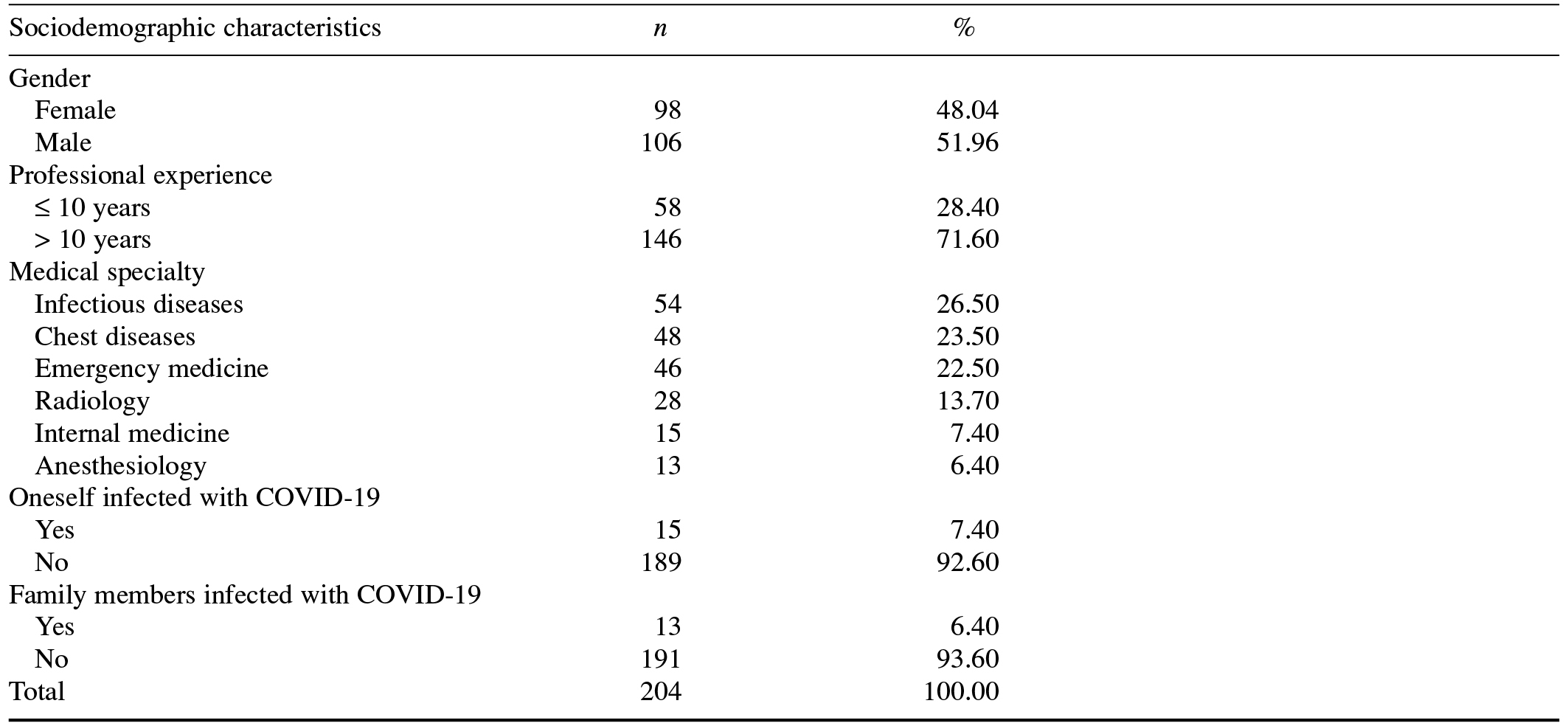

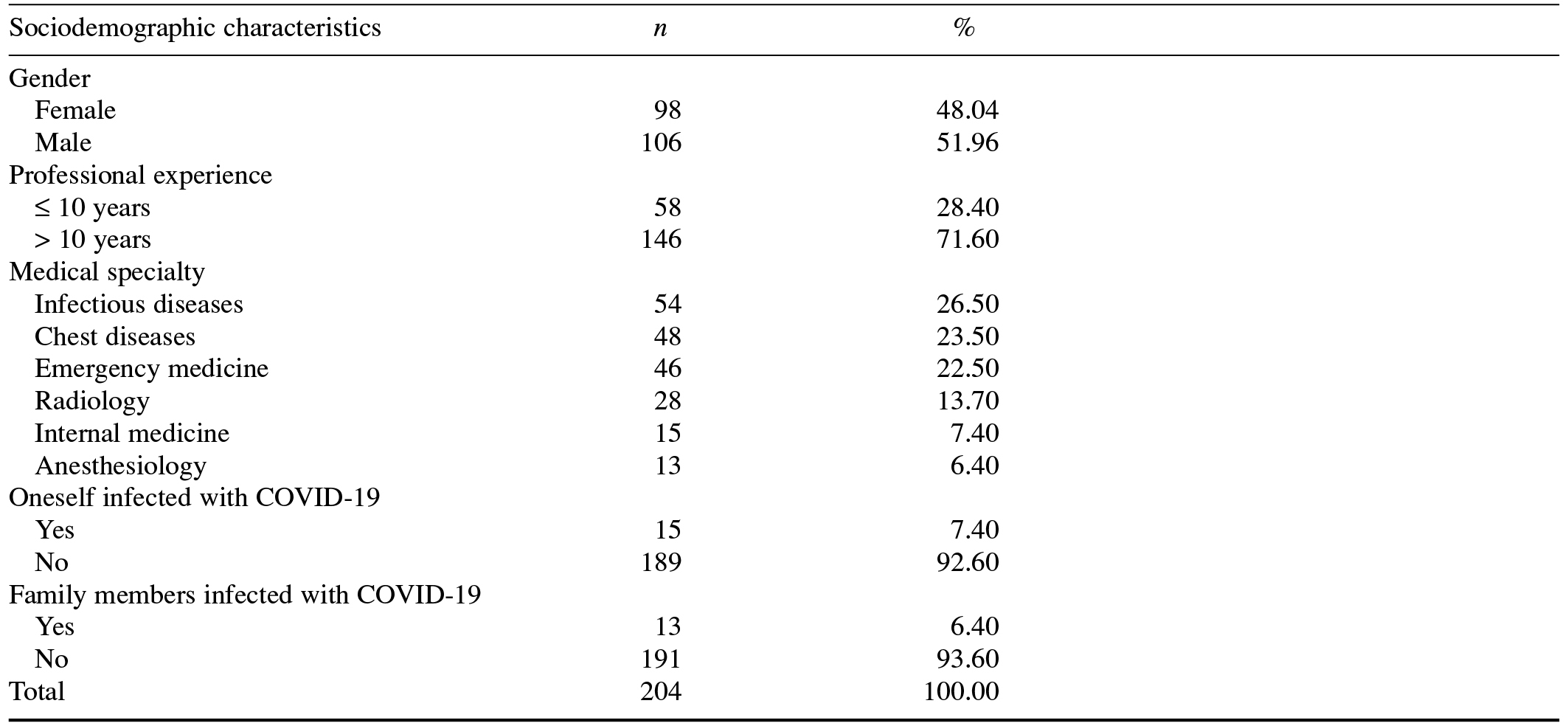

We used a qualitative, case study approach (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016) in this study. Participants comprised 204 medical doctors registered with the Health Sciences University in Istanbul and working at 40 education and research hospitals affiliated with the Turkish Ministry of Health, which were located across 15 provinces of Turkey. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1. Participants’ Sociodemographic Characteristics

Procedure

This study was reviewed by and received ethical approval from the rectorate of the Health Sciences University, Istanbul, and we were permitted to conduct our research with medical doctors working at education and research hospitals affiliated with the Turkish Ministry of Health (Official/Special Permission Document No. E13719, dated April 27, 2020). Between May 28 and June 5, 2020, we used a semistructured survey consisting of the two open-ended research questions as a data collection tool. Before starting the study, all of the participants were provided with the necessary briefings, and their approval and consent were acquired. We forwarded the research questions via email and respondents provided a Microsoft Word document containing their written responses.

Data Analysis

We used an adaptation of the content analysis technique to examine our data. Two major themes were generated based on the two questions asked of the participants: (a) psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and (b) strategies employed to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. The views of the participants relating to the two major themes were explained systematically through interpretation of their responses, with some results achieved through examining cause-and-effect relationships. We read each survey one by one and encoded the participant’s responses according to the two identified major themes. Next, we created subthemes under each of the two major themes. A frequency value for each of these subthemes was established and reported in tabular format. This process was separately conducted by two different researchers according to similarity/dissimilarity of responses for each theme. The codes and categories formed by each researcher following their analyses were compared and assessed, and finally a consensus was reached. An agreement percentage formula was applied to determine the reliability of the content analysis process: reliability = agreement ÷ (agreement + disagreement) × 100 (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Interrater agreement was 87% for the first theme and 85% for the second theme, and the overall interrater agreement for both themes was 86%.

Results

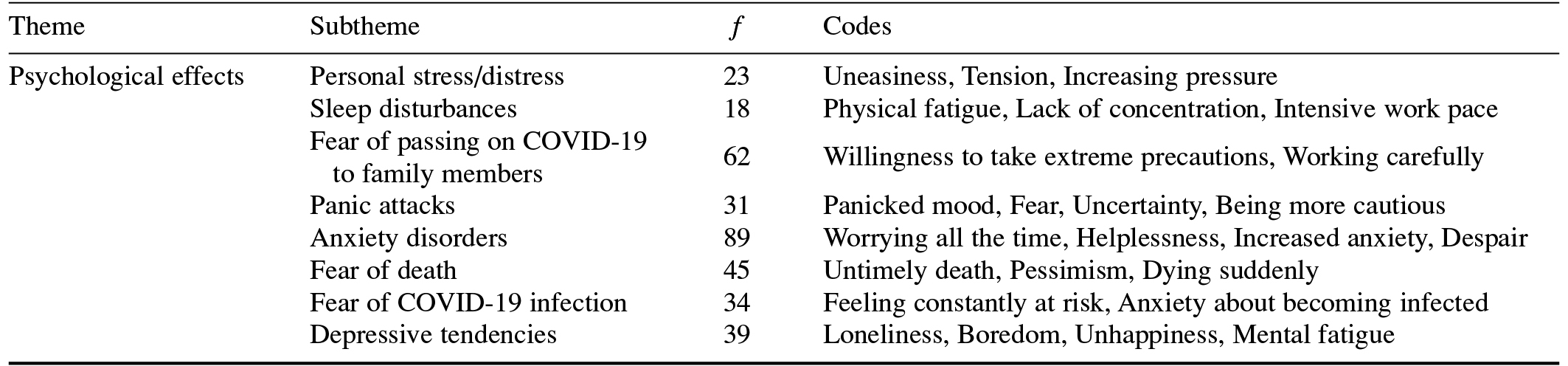

Theme 1: Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic

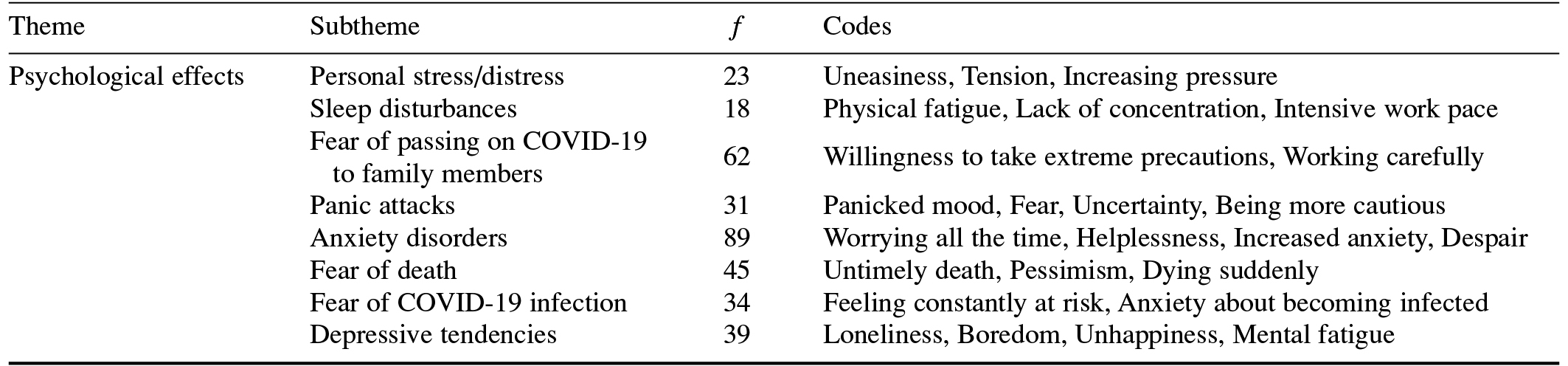

The first of the two major themes is the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the participant medical doctors. Their views and thoughts regarding the theme are divided into eight subthemes, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Medical Doctors

Following is a selection of direct quotations from the participants regarding the personal stress/distress subtheme: “…I constantly feel under pressure while working in the hospital” [K7], “…My stress level increases exponentially when my Emergency Department duty approaches” [K133], and “…The stress I experience increases the risk of making mistakes” [K201].

The participants’ views regarding the sleep disturbances subtheme were as follows: “I have encountered an intense work pace that I find difficult to cope with. Some days I even have difficulty in sleeping due to extreme fatigue” [K19]; “…During the pandemic, our social life and sleep patterns are disturbed” [K117]; and “…[The] excessive workload constantly increases the pressure I feel, and even causes me to lose sleep” [K120].

The participants’ views regarding the fear of passing on COVID-19 to family members subtheme were as follows: “…So as not to risk my family members’ lives, I stayed at a hotel for 20 days as a precautionary measure” [K113]; and “I have had to live in a different house for a long time due to the fear of being infected and [then] passing the disease on to my family members” [K158].

The participants’ views regarding the panic attacks subtheme were as follows: “…There is a completely uncontrolled atmosphere of panic in the hospital” [K81]; “While working in the Emergency Department of the hospital, I have constant feelings of panic and fear” [K95]; and “…While reading [social media] posts regarding the pandemic, I experience sudden and extreme moments of panic” [K193].

The participants’ views regarding the anxiety disorders subtheme were as follows: “The fear that anything bad might happen to my family during the pandemic causes me serious anxiety” [K77], “…I am constantly anxious since I am coping with a [potentially] fatal disease” [K126], and “…I experience anxiety about my family from time to time” [K169].

The participants’ views regarding the fear of death subtheme were as follows: “…I am afraid of dying, and I feel anxious as I do not know who will look after my family if anything bad happens to me” [K8]; “I am afraid of being infected with COVID-19 and then dying, and I am having difficulty coping with this issue” [K99]; and “…I am experiencing a severe fear of death” [K162].

The participants’ views regarding the fear of COVID-19 infection subtheme were as follows: “…Almost every day I feel anxiety that I will be infected with the disease” [K28]; “Like many of my colleagues, I am extremely afraid of being infected” [K36]; and “…While working in the Emergency Department, I always feel fearful of becoming infected” [K163].

The participants’ views regarding the depressive tendencies subtheme were as follows: “…I have begun to notice symptoms of depression [in myself]” [K88]; “I have particularly started to worry [about] if I am going to become infected, or that my family will be distressed if I am infected” [K92]; and “…When I go to work, I feel my pulse rising and atrial fibrillation starts…” [K190].

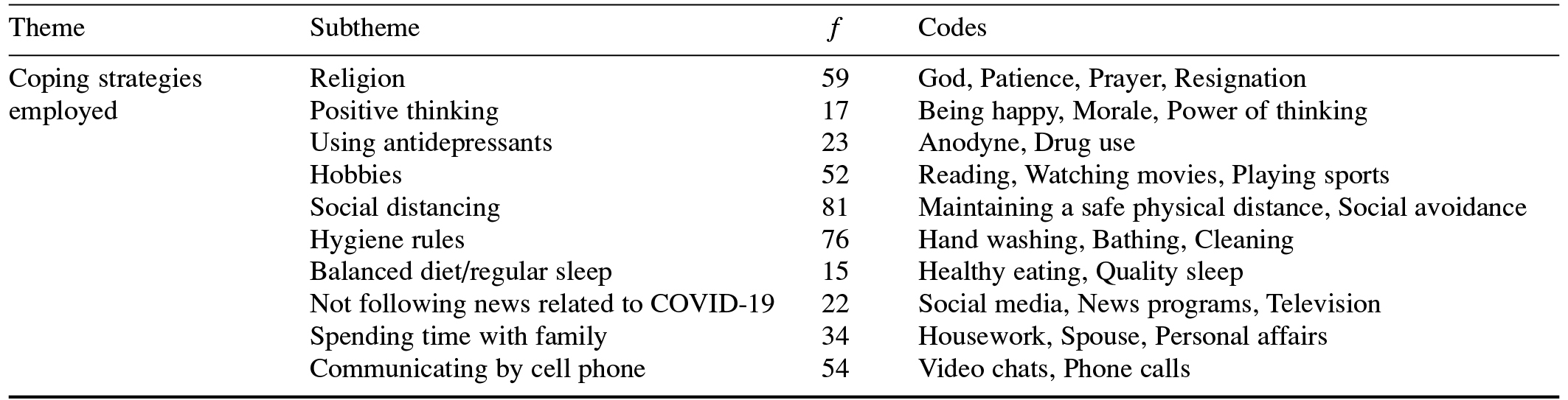

Theme 2: Strategies Employed to Cope With the COVID-19 Pandemic

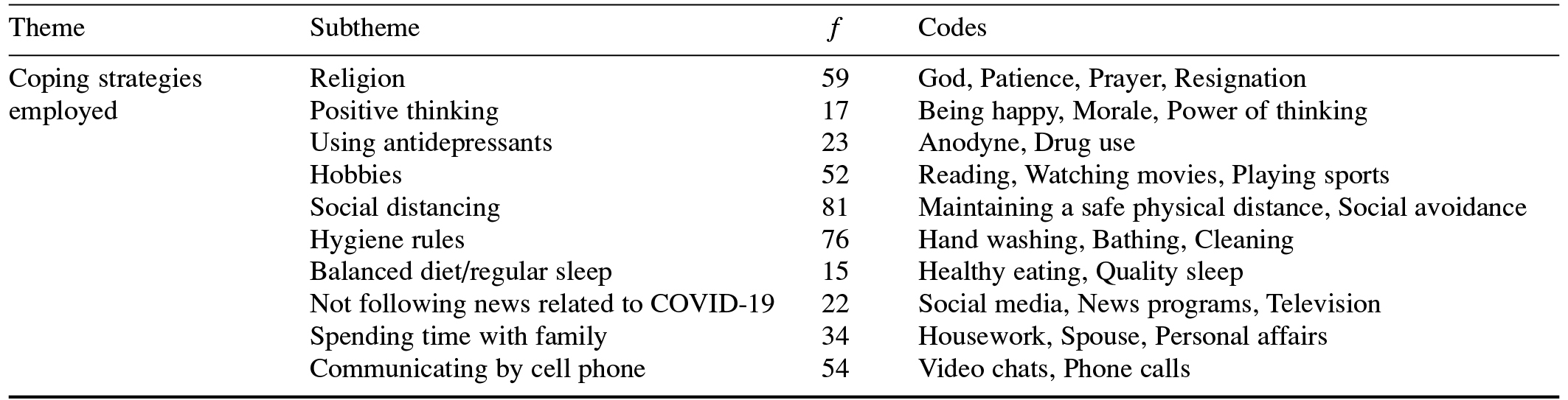

The second major theme is the strategies employed by the participant medical doctors to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. Their views and thoughts are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Strategies Employed by Medical Doctors to Cope With the COVID-19 Pandemic

Following is a selection of direct quotations from the participants regarding the religion subtheme: “…I pray to God and wait patiently, hoping that these [pandemic] days will pass” [K21]; “…First, I take reasonable measures to prevent COVID-19, and then I try to trust in Allah” [K39]; “…I take all reasonable precautions and pray to Allah” [K84]; “…I always pray to Allah” [K96]; and “…There is nothing I can do except forbearance and prayer” [K144].

The participants’ views regarding the positive thinking subtheme were as follows: “…I always try to think positively about the disease as much as possible” [K11]; “I try to think positively regarding the process [of fighting COVID-19] by leaving negative feelings and thoughts about the disease aside” [K41]; and “…So I try to avoid being pessimistic about the pandemic through focusing on positive thoughts” [K119].

The participants’ views regarding the using antidepressants subtheme were as follows: “…I try to remain calm and use antidepressants to keep my psychological well-being strong” [K16]; “I have difficulty in coping with the pandemic psychologically. I have begun to use antidepressants” [K108]; and “I had to start using antidepressants because I couldn’t cope with the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic” [K196].

The participants’ views regarding the hobbies subtheme were as follows: “I do sports regularly, read books, and listen to music” [K1]; “…Doing sports as much as possible, and reading” [K15]; and “…I read more books and watch movies” [K57].

The participants’ views regarding the social distancing subtheme were as follows: “I meet with my colleagues in the hospital, but pay attention to social distancing and wear a face mask” [K6]; “I try to approach patients more cautiously within the framework of social distancing rules” [K73]; and “…We have fewer social activities, and meetings with fewer participants…” [K164].

The participants’ views regarding the hygiene rules subtheme were as follows: “…I pay more attention to hand hygiene. I always use personal protective equipment” [K10]; and “…I pay more attention to the use of personal protective equipment and hand hygiene” [K69].

The participants’ views regarding the balanced diet/regular sleep subtheme were as follows: “…I am very careful about sleeping regularly every day. I try to have a balanced diet” [K20]; and “…In this [pandemic] period, I strive to maintain a healthy and balanced diet to keep my immune system strong” [K42].

The participants’ views regarding the subtheme of not following news related to COVID-19 were as follows: “…Listening to statements made about COVID-19 bothers me now” [K58], and “I do not watch news items about COVID-19” [K71].

The participants’ views regarding the spending time with family subtheme were as follows: “…I try to spend more time with my family as much as possible” [K14], and “I engage in various activities to spend more quality time with my children at home” [K43].

The participants’ views regarding the communicating by cell phone subtheme were as follows: “…I try to boost my children’s, my wife’s, and my parents’ morale by talking to them over the phone” [K54]; and “…I have reached out to all my friends and acquaintances over the phone and talk to them very often…” [K98].

Discussion

This study analyzed the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical doctors working in Turkish hospitals assigned to treat patients infected with the coronavirus. Various studies have emphasized that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the amount of psychological pressure on health professionals as well as the associated physical symptoms they experience (Cullen et al., 2020; Huang & Zhao, 2020a; Y. Wang et al., 2020). When we examined the responses of our participants, anxiety disorders (f = 89), fear of passing on COVID-19 to family members (f = 62), and fear of death (f = 45) were the most commonly mentioned among eight psychological effect subthemes we identified.

Our findings show that anxiety disorders had the strongest psychological effect on medical doctors. Chew et al. (2020) reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic, some healthcare professionals experienced severe anxiety and depression, and others experienced moderate stress or psychological distress. Sun et al. (2020) found that the negative feelings of healthcare professionals about the coronavirus during the early stages of the pandemic caused them to experience high levels of anxiety and fear. In another study on the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cao et al. (2020) reported that the majority of their participants experienced severe anxiety during the pandemic period. Similarly, C. Wang et al. (2020) found that the pandemic caused psychological problems, such as anxiety and depression, in some people. These previous results largely parallel the views of the medical doctors we interviewed, who expressed their opinions regarding the negative psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We further found that fear of death and fear of passing on COVID-19 to family members were major psychological effects experienced by medical doctors. Some of our participants stated their concern about being infected with the COVID-19 virus and then inadvertently passing it on their family, and reported that they held a significant fear of contracting and subsequently dying from the disease. Mukhtar (2020) stated that, as with other infectious disease outbreaks, the COVID-19 pandemic caused a fear of death and a sense of despair. Moreover, Ornell et al. (2020) emphasized that the pandemic triggered a concrete fear of death as well as a sense of despair. During such outbreaks of disease, serious concerns may develop among patients, such as fear of death and a sense of loneliness (Zandifar & Badrfam, 2020). From this perspective, it can be said that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected not only the physical health of the population, but also their mental health and well-being.

Other psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that our participants emphasized were depressive tendencies, fear of infection, panic attacks, personal stress/distress, and sleep disturbances. According to Qiu et al. (2020), the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a wide range of psychological problems, such as panic attacks, stress, anxiety, and depression. W. Zhang et al. (2020) obtained similar results, reporting that healthcare workers and professionals fighting the pandemic experienced symptoms of depression, stress, and severe insomnia. Furthermore, Huang and Zhao (2020a) stated that their participants exhibited symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety, along with signs of poor sleep. Liu et al. (2020) also found that the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected some people’s sleep quality. Finally, Huang and Zhao (2020b) observed that healthcare workers and professionals experienced a poorer quality of sleep due to the stress and depressive symptoms they experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic period. These results indicate that psychological problems, such as fear, stress, and panic, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic pose a significant risk to the mental health of medical doctors.

When we classified the opinions of our participants regarding the strategies they employed to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing (f = 81), following hygiene rules (f = 76), and religion (f = 59) were the top three subthemes. Shim et al. (2020) emphasized that measures such as social distancing and following hygiene rules should be implemented to more quickly control the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Dein et al. (2020) highlighted the role of religiously related behavior in dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, adherents of many religions around the world gathered together to pray for an end to the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of medical doctors we interviewed stated that after taking all precautions to protect against COVID-19, they prayed for an end to the pandemic. Prayer, which has an important place in religious beliefs that accept the intervention of a deity in their life, constitutes the central phenomenon of religion. During the COVID-19 pandemic, prayer was recommended to strengthen the religious and spiritual feelings of people (Presidency of Religious Affairs, 2020). Thus, religious officials read prayers in the mosques in Turkey for the treatment of patients and an end to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other strategies that medical doctors employed to cope with the pandemic were communicating by cell phone, undertaking hobbies, spending time with family, using antidepressants, not following news related to COVID-19, positive thinking, and having a balanced diet/regular sleep. Lades et al. (2020) found that participants who had to spend most of their time at home during the pandemic tried to take advantage of this period positively and effectively by spending time with their family. Further, Y. Zhang and Ma (2020) observed that their participants sought increased support from and connection with their family members during the pandemic. The medical doctors in our study similarly mentioned spending quality time with their family members, undertaking activities such as exercising, following hobbies, and taking care of their family and children while they were staying at home during the pandemic period.

Finally, our participants asserted that they generally tried not to follow news relating to COVID-19 to avoid the negative psychological effects of the pandemic. Lades et al. (2020) suggested that limiting media monitoring about the COVID-19 disease could play a protective role in preserving people’s comfort and well-being during the pandemic. Mamun and Griffiths (2020) further emphasized the significance of avoiding unreliable news and information resources as a means of reducing unnecessary feelings of fear and panic related to stories about COVID-19. Some of the medical doctors who participated in this study also took antidepressants to increase their psychological resistance, so as to better cope with the pandemic. According to Brietzke et al. (2020), increased usage of antidepressants during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates there is a relationship between viral infections and mood disorders. During a period where an infectious disease is known to be spreading, the psychological reactions that people exhibit play a critical role in the development of emotional distress symptoms. Therefore, the psychological and psychiatric needs of people should be taken into account at every stage of a pandemic (Cullen et al., 2020). Hence, antidepressant medication may have helped medical doctors to relax both psychologically and physically by reducing the intense feelings of stress and anxiety experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has some limitations. Our use of an exploratory, descriptive, qualitative research design means the sample size was small. To perform a more comprehensive assessment of the wider effects of the COVID-19 epidemic, further research could be conducted on larger samples, and the experiences of health professionals from different areas or branches could be included. Furthermore, a mixed-methods research approach encompassing both quantitative and qualitative paradigms could be implemented in future research studies in this area.

Conclusion

This study provides an in-depth and detailed examination of the psychological experiences of medical doctors working on the frontline of the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. We found that medical doctors experienced increased psychological problems, such as personal stress, depressive tendencies, anxiety, fear, panic attacks, and sleep disorders. To cope with the pandemic, these medical doctors used strategies such as practicing religious beliefs, thinking positively, using antidepressants, undertaking hobbies, paying attention to safe physical distancing and hygiene rules, eating a balanced and healthy diet, sleeping regularly, purposefully not following news reports about COVID-19, spending quality time with their family, and talking with their loved ones more over the phone. Our findings show there is an urgent need to develop appropriate intervention strategies and policies to increase the psychological resistance of medical doctors working to fight COVID-19, by helping them to cope with the pandemic more effectively, and by protecting and improving their physical and psychological health.

References

Brietzke, E., Magee, T., Freire, R. C. R., Gomes, F. A., & Milev, R. (2020). Three insights on psychoneuroimmunology of mood disorders to be taken from the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, 5, Article 100076.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100076

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, Article 112934.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Chew, N. W.-S., Lee, G. K.-H., Tan, B. Y.-Q., Jing, M., Goh, Y., Ngiam, N. J.-H., … Sharma, V. K. (2020). A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 559–565.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049

Cullen, W., Gulati, G., & Kelly, B. D. (2020). Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(5), 311–312.

https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110

Dein, S., Loewenthal, K., Lewis, C. A., & Pargament, K. I. (2020). COVID-19, mental health and religion: An agenda for future research. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(1), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1768725

Fava, G. A., McEwen, B. S., Guidi, J., Gostoli, S., Offidani, E., & Sonino, N. (2019). Clinical characterization of allostatic overload. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 108, 94–101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.05.028

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020a). Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Who will be the high-risk group? Psychology, Health & Medicine. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020b). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, Article 112954.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

Hui, D. S., Azhar, E. I., Madani, T. A., Ntoumi, F., Kock, R., Dar, O., … Petersen, E. (2020). The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 91, 264–266.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009

Lades, L. K., Laffan, K., Daly, M., & Delaney, L. (2020). Daily emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Health Psychology. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12450

Liu, N., Zhang, F., Wei, C., Jia, Y., Shang, Z., Sun, L., … Liu, W. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China [sic] hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Research, 287, Article 112921.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921

Mamun, M. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: Possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, Article 102073.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Wiley.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

Mukhtar, S. (2020). Mental health and emotional impact of COVID-19: Applying health belief model for medical staff to general public of Pakistan. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 28–29.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.012

Ornell, F., Schuch, J. B., Sordi, A. O., & Kessler, F. H. P. (2020). “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008

Presidency of Religious Affairs. (2020). President of Religious Affairs Erbas prayed from Kocatepe Mosque [In Turkish]. https://bit.ly/37ieKof

Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry, 33(2), e100213.

https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

Ren, L.-L., Wang, W.-M., Wu, Z.-Q., Xiang, Z.-C., Guo, L., Xu, T., … Wang, J.-W. (2020). Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: A descriptive study. Chinese Medical Journal, 133(9), 1015–1024.

https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000000722

Shim, E., Tariq, A., Choi, W., Lee, Y., & Chowell, G. (2020). Transmission potential of COVID-19 in South Korea. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 93, 339–344.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.031

Sun, N., Wei, L., Shi, S., Jiao, D., Song, R., Ma, L., … Wang, H. (2020). A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control, 48(6), 592–598.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018

Turkish Medical Association. (2020, April 22). The number of healthcare professionals diagnosed with the COVID-19 is increasing [In Turkish]. https://bit.ly/2Hk2Uza

Turkish Ministry of Health. (2020a). New coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [In Turkish]. https://bit.ly/3nZIhJg

Turkish Ministry of Health. (2020b). Current situation in Turkey (coronavirus) [Live data] [In Turkish]. https://bit.ly/2Hk2WXO

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), Article 1729.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

Wang, Y., Di, Y., Ye, J., & Wei, W. (2020). Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychology, Health & Medicine. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817

World Health Organization. (2020a). Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://bit.ly/31krd75

World Health Organization. (2020b, July 31). Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://bit.ly/2T3sHxR

Zandifar, A., & Badrfam, R. (2020). Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, Article 101990.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990

Zhang, W., Wang, K., Yin, L., Zhao, W., Xue, Q., Peng, M., … Wang, H. (2020). Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 89(4), 242–250.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000507639

Zhang, Y., & Ma, Z. F. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), Article 2381.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072381

Zhu, N., Zhang, D., Wang, W., Li, X., Yang, B., Song, J., … Tan, W. (2020). A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(8), 727–733.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

Brietzke, E., Magee, T., Freire, R. C. R., Gomes, F. A., & Milev, R. (2020). Three insights on psychoneuroimmunology of mood disorders to be taken from the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, 5, Article 100076.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100076

Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, Article 112934.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Chew, N. W.-S., Lee, G. K.-H., Tan, B. Y.-Q., Jing, M., Goh, Y., Ngiam, N. J.-H., … Sharma, V. K. (2020). A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 559–565.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049

Cullen, W., Gulati, G., & Kelly, B. D. (2020). Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(5), 311–312.

https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110

Dein, S., Loewenthal, K., Lewis, C. A., & Pargament, K. I. (2020). COVID-19, mental health and religion: An agenda for future research. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(1), 1–9.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1768725

Fava, G. A., McEwen, B. S., Guidi, J., Gostoli, S., Offidani, E., & Sonino, N. (2019). Clinical characterization of allostatic overload. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 108, 94–101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.05.028

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020a). Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: Who will be the high-risk group? Psychology, Health & Medicine. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020b). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, Article 112954.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

Hui, D. S., Azhar, E. I., Madani, T. A., Ntoumi, F., Kock, R., Dar, O., … Petersen, E. (2020). The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 91, 264–266.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009

Lades, L. K., Laffan, K., Daly, M., & Delaney, L. (2020). Daily emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Health Psychology. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12450

Liu, N., Zhang, F., Wei, C., Jia, Y., Shang, Z., Sun, L., … Liu, W. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China [sic] hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Research, 287, Article 112921.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921

Mamun, M. A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). First COVID-19 suicide case in Bangladesh due to fear of COVID-19 and xenophobia: Possible suicide prevention strategies. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, Article 102073.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102073

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Wiley.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

Mukhtar, S. (2020). Mental health and emotional impact of COVID-19: Applying health belief model for medical staff to general public of Pakistan. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 28–29.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.012

Ornell, F., Schuch, J. B., Sordi, A. O., & Kessler, F. H. P. (2020). “Pandemic fear” and COVID-19: Mental health burden and strategies. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0008

Presidency of Religious Affairs. (2020). President of Religious Affairs Erbas prayed from Kocatepe Mosque [In Turkish]. https://bit.ly/37ieKof

Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry, 33(2), e100213.

https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

Ren, L.-L., Wang, W.-M., Wu, Z.-Q., Xiang, Z.-C., Guo, L., Xu, T., … Wang, J.-W. (2020). Identification of a novel coronavirus causing severe pneumonia in human: A descriptive study. Chinese Medical Journal, 133(9), 1015–1024.

https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000000722

Shim, E., Tariq, A., Choi, W., Lee, Y., & Chowell, G. (2020). Transmission potential of COVID-19 in South Korea. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 93, 339–344.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.031

Sun, N., Wei, L., Shi, S., Jiao, D., Song, R., Ma, L., … Wang, H. (2020). A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control, 48(6), 592–598.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018

Turkish Medical Association. (2020, April 22). The number of healthcare professionals diagnosed with the COVID-19 is increasing [In Turkish]. https://bit.ly/2Hk2Uza

Turkish Ministry of Health. (2020a). New coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [In Turkish]. https://bit.ly/3nZIhJg

Turkish Ministry of Health. (2020b). Current situation in Turkey (coronavirus) [Live data] [In Turkish]. https://bit.ly/2Hk2WXO

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), Article 1729.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

Wang, Y., Di, Y., Ye, J., & Wei, W. (2020). Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychology, Health & Medicine. Advance online publication.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1746817

World Health Organization. (2020a). Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. https://bit.ly/31krd75

World Health Organization. (2020b, July 31). Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://bit.ly/2T3sHxR

Zandifar, A., & Badrfam, R. (2020). Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, Article 101990.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990

Zhang, W., Wang, K., Yin, L., Zhao, W., Xue, Q., Peng, M., … Wang, H. (2020). Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 89(4), 242–250.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000507639

Zhang, Y., & Ma, Z. F. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), Article 2381.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072381

Zhu, N., Zhang, D., Wang, W., Li, X., Yang, B., Song, J., … Tan, W. (2020). A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(8), 727–733.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

Table 1. Participants’ Sociodemographic Characteristics

Table 2. Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Medical Doctors

Table 3. Strategies Employed by Medical Doctors to Cope With the COVID-19 Pandemic

Turgut Karakose, Faculty of Education, Department of Educational Administration, Kutahya Dumlupinar University, Evliya Celebi Campus, 43100, Kutahya, Turkey. Email: [email protected]