Influence of sensory experiences on tourists’ emotions, destination memories, and loyalty

Main Article Content

We examined the influence of tourists’ sensory experiences on their destination loyalty, and the mediating effects of tourists’ emotions and memories of their experience. Data were collected using a self-report survey from 304 tourists visiting Wuyi Mountain, a natural and cultural World Heritage Site in China. We found positive impacts of sensory experiences on emotions, memories, and loyalty; of emotions on memories and loyalty; and of experience memories on loyalty. Further, sensory experiences increased tourists’ loyalty by positively influencing their memories, and sensory experiences positively affected tourists’ memories by arousing their emotions, thereby affecting their loyalty. Our findings provide a deeper understanding of the internal mechanism of stimulating sensory experiences for enhancing tourist loyalty. Avenues for engaging tourists should address the effect of sensory experiences on emotions and destination memories.

Tourism experiences are key factors in the formation of tourist destination loyalty (Chi & Qu, 2008), and are multidimensional structures that include physical, emotional, social, and cognitive knowledge experiences. Agapito et al. (2017) summarized the findings of previous studies and concluded that among the different types of tourist experiences, sensory experiences are the most important and the most crucial (Gentile et al., 2007). Therefore, exploring the relationship between tourists’ sensory experiences and their destination loyalty can be a foundation for sustainable destination development and enhanced tourist experiences.

The sensory organs, namely, the eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and skin, are the channels through which people obtain information from the outside world, and are the bases for the formation of perceptions and psychological activities. Conscious sensory experiences refer to the perception of the selection, organization, and interpretation of sensory input information (Goldstein, 2010). In the context of tourism, sensory experiences are important because sensory stimulation integrates environmental factors into the consumption of tangible products or intangible services (Heide & Grønhaug, 2006). Further, tourists’ experiences originate from a series of interactions between them and different environments, and these interactions involve at least one sensory organ (Agapito et al., 2017). Prior studies have indicated the importance of tourists’ sensory experiences in enhancing both the whole tourism experience and destination loyalty. However, research on sensory experiences in the tourism context remains limited (Agapito et al., 2013; Kirillova et al., 2014). In a study exploring the relationships between tourists’ sensory impressions and their destination loyalty, Lu et al. (2019) found that sensory impressions play only a partial role as a direct explanation of destination loyalty. Thus, these authors concluded that the mechanism of the effect of sensory impressions on tourist loyalty is complex, and other intermediary variables must be identified to fully distinguish the internal mechanism between sensory experiences and tourist loyalty.

Emotional experience is an aroused or activated feedback state that an individual produces in response to external stimuli (Feng, 2010). Tourists’ emotions are an antecedent variable used as an important predictor of evaluations and behaviors (Xu et al., 2018). Regarding the process of emotional experience generation, Davitz (1969) pointed out that people form psychological and emotional evaluations after receiving external stimuli. For example, the environment a person perceives when shopping (e.g., lighting, smell, and sound; Yüksel, 2007), or the physical, social, personal, and temporal factors tourists process in travel situations (Xu et al., 2018), all have an influence on their emotional state.

At the operational level, J.-H. Kim et al. (2010) defined tourism experience memories as tourism experiences that can be remembered and recalled easily afterwards. On the basis of the theory of perception, J.-H. Kim et al. discussed how the experiential factors of involvement and refreshing experiences increase an individual’s ability to vividly recollect and retrieve past travel experiences. Alternatively, the experience of local culture enhances the recollection of past travel experiences. Pan et al. (2016) found that hedonism, novelty, and involvement all have a positive effect on the recollection of tourism experience memories, and that experiencing the local culture has a positive influence on the vividness of tourism experience memories.

From the perspective of consumers’ product loyalty, Chen and Gursoy (2001) defined tourist loyalty as tourists’ commitment to a destination, which is reflected in their revisit intention and public recommendation of that destination. In terms of its structural dimensions, scholars have divided tourist loyalty into two dimensions: attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty (Bonn et al., 2007; H. Chen & Rahman, 2018). The attitudinal dimension comprises a specific desire to continue a relationship with a product/service provider, and the behavioral dimension refers to repeated visits (C.-F. Chen & Chen, 2010). In this study we used attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty to measure tourists’ loyalty to the natural and cultural World Heritage Site of Wuyi Mountain, China.

Using the information received through their sensory organs, people can form either positive or negative opinions of their experiences (Mehraliyev et al., 2020). These sensory experience evaluations can change the individual’s emotional state (H.-T. Chen & Lin, 2018) and also influence the formation of long-term memories of the experience (Agapito et al., 2017). However, the relationships of sensory experiences, emotions, memories, and loyalty have not been thoroughly investigated in the context of tourism. Because tourists’ sensory experiences have significant theoretical and practical implications for experience quality improvement, destination loyalty management, and sustainable development, the effect of these sensory experiences on loyalty and the inner influencing route needs to be examined empirically.

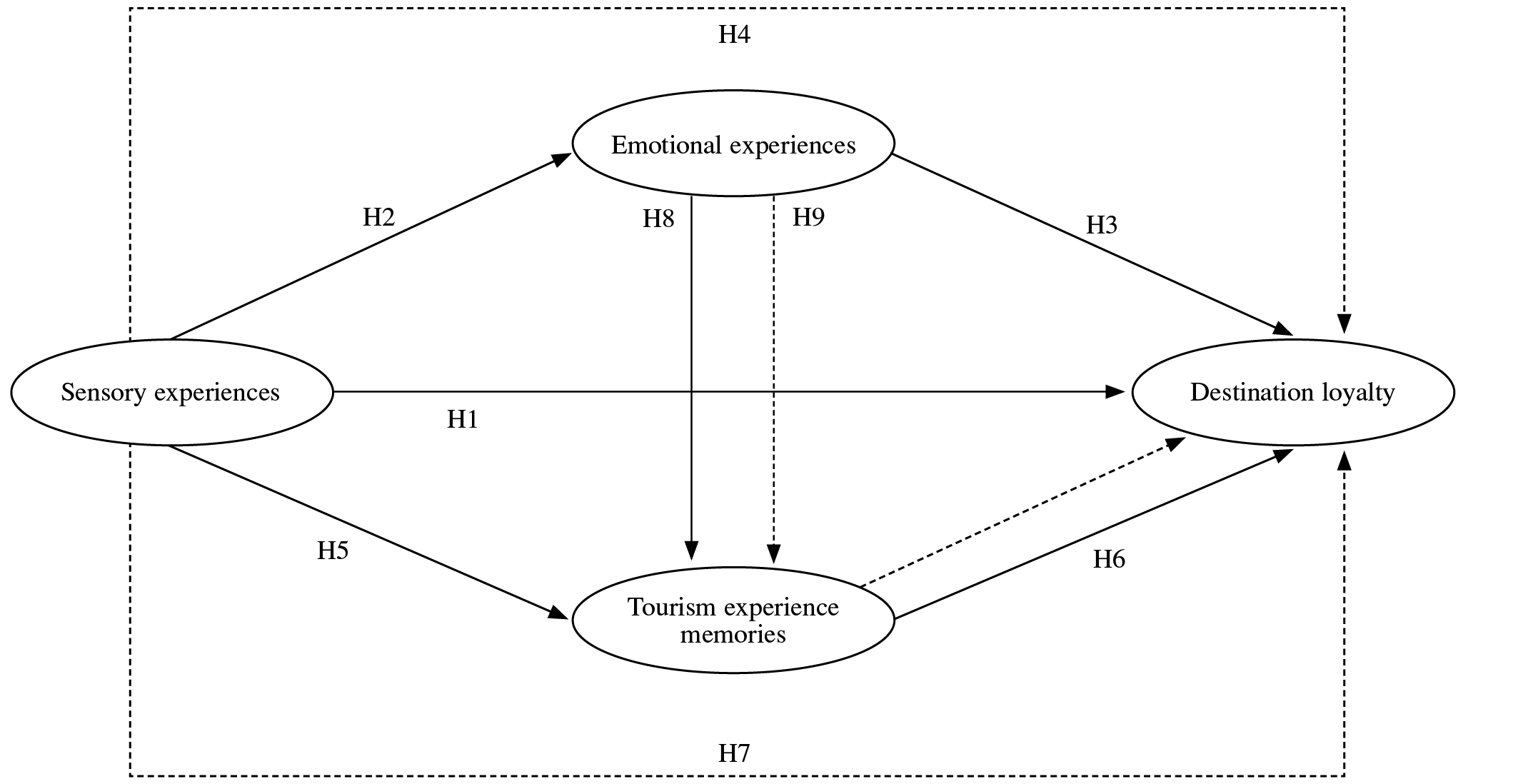

The specific objectives of this study were (a) to construct a model of the inner function routes between sensory experience and tourists’ loyalty by using the theories of embodied cognition (Barsalou, 1999) and sensory marketing (Krishna, 2013), and (b) to empirically test the relationships of tourists’ sensory experiences, their induced emotions and memories, and destination loyalty, so as to provide further theoretical guidance for promoting destination loyalty and tourist experience quality management.

Theoretical Background

The transformation of cognitive science to the embodiment paradigm is based on rejection of the body–mind dualism, emphasizing that human subjectivity is formed through the interaction between the physical body and the external world, and that body, mind, and environment are an integral system that cannot be separated. This paradigm returns attention to the human body, emphasizing the close connection between physical experience and psychology (Niedenthal et al., 2005). Physical experiences can activate people’s psychological feelings and then influence their behavioral intentions (Barsalou, 2008). Grounded cognitive theory (Barsalou, 2008) highlights sensory marketing consumers’ mental processing of information. Consumers’ multisensory experience influences their attitudes and behaviors by affecting their cognitive emotions and memories (Krishna, 2012). Krishna (2013) also suggested that sensory stimulation can directly affect consumers’ buying behavior.

The two theories of embodied cognition and sensory marketing explain the physiological and psychological mechanisms behind consumer attitudes and behaviors. In the context of tourism, perceptions of a tourist destination come from not only the direct stimulation of the tourists’ senses, but also from mental processing caused by sensory stimulation. In the interpretation of tourist destination loyalty, tourists’ senses and mental experiences each have their own advantages, and marketers and tourism developers should pay attention to both (Lu et al., 2019). Therefore, in view of these two mechanisms identified in marketing theory on consumer attitudes and behaviors, we explored the relationships between tourists’ sensory experiences, emotions, experience memories, and destination loyalty, in order to deepen understanding of the internal functional relationships between tourists’ sensory experiences and their destination loyalty.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Through continuing exploration of the sensory–psychological connection, marketers have begun paying increasing attention to the role of sensory experiences in marketing. Agapito et al. (2017) conducted a study in a setting characterized by maritime and inland scenery and rural lodgings, to explore the impact of sensory experiences on tourists’ loyalty. Their findings suggest that sensorially rich experiences have an important role in encouraging favorable tourist behavior toward a destination. On this basis, Lu et al. (2019) utilized three interrelated studies, comprising a content analysis of online reviews, a field experiment, and an online survey, to test the impact of sensory impressions on tourists’ destination loyalty. Their findings show that sensory impressions are physical memories caused by sensory stimulation, which can directly affect the behavior of tourists. On the basis of this concept, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The sensory experiences of tourists at a cultural and natural World Heritage Site will have a significant positive impact on their destination loyalty.

In sensory marketing theory the focus is on how consumers interact with the outside world through their senses, which, in turn, affects their emotions, attitudes, memories, and behaviors (Krishna, 2012). Qiu et al. (2017) took cell phone use as an example to analyze the impact of experience of different products on consumers’ loyalty, and found that consumers’ sensory experiences with the design, color, and texture of the phones affected consumers’ experience of pleasant emotions and their loyalty to the product.

Customer emotions are an important factor for understanding their perception of the service experience (Mattila & Enz, 2002; Oliver et al., 1997; Richins, 1997). Thus, having pleasant experiences plays an important role in building customer loyalty (Hicks et al., 2005; Torres & Kline, 2006). However, thus far there has been a limited amount of empirical research on the relationship between customers’ emotions and loyalty (M. Kim et al., 2013). Lin and Liang (2011) explored the relationships among the service environment, and customers’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty, and concluded that joy has a positive effect on the loyalty of customers. Ali et al. (2018) used a Malaysian theme park as an example and showed that when customers felt joy, this had a significant positive impact on their loyalty. Ali et al. suggested that theme park managers should pay attention to maintaining a good physical setting to ensure that customers’ experiences are delightful.

In addition, Liu et al. (2010) established direct and indirect impact models of tourists’ perception of the colors, lighting, sounds, and smells in a shopping environment on their shopping behavior. Findings suggest that the perceived shopping environment impacts on tourists’ shopping behavior by changing their shopping mood, and that tourist shopping mood plays an important mediating role in the path of environment–emotion–behavior. On the basis of these findings, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2: The sensory experiences of tourists at a cultural and natural World Heritage Site will have a significant positive impact on their emotions.

Hypothesis 3: The emotions of tourists at a cultural and natural World Heritage Site will have a significant positive impact on their loyalty.

Hypothesis 4: Tourists’ emotions at a cultural and natural World Heritage Site will have a mediating effect in the relationship between their sensory experiences and their loyalty.

Travel experiences positively affect memories (Oh et al., 2007). Ballantyne et al. (2011) recorded memories of wildlife tourism experiences and found that the tourists who took part in their study reported vivid visual, auditory, olfactory, and/or tactile-related memories. Wang (2017) examined the use of multisensory experiences in the context of museum exhibits and concluded that the addition of such experiences can enhance the audience’s sense of presence and immersion, thereby creating strong impressions and visit memories. On the basis of these findings, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5: The sensory experiences of tourists at a cultural and natural World Heritage Site will have a significant positive impact on their travel experience memories.

Oh et al. (2007) found that tourists’ memories of an experience significantly affect their satisfaction and their behavioral intention. Knutson et al. (2010) also determined that customer experiences in the hospitality industry affect their recollections of the experience, which, in turn, influence their satisfaction and willingness to revisit. Quadri-Felitti and Fiore (2012) used wine tourism experiences as their research context and found that tourists’ memories of their experience have a positive and significant influence on their level of satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Hosany and Witham (2010) took cruise vacations as their research background and found that passengers’ memories of their cruise experience have a significant positive impact on their satisfaction and recommendation intentions. On the basis of these findings, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6: Tourists’ travel experience memories of a cultural and natural World Heritage Site will have a significant positive impact on their destination loyalty.

In addition, travel experiences can arouse tourists’ physical feelings (senses of body; e.g., sensory feelings) and psychological feelings (positive or negative emotions), and affect consumers’ future decision-making behaviors by leaving deep impressions and generating positive opinions (Pine & Gilmore, 2011). Consumer experience dimensions exert positive effects on their memories, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions (Dolcos & Cabeza, 2002; Hosany & Witham, 2010). Agapito et al. (2017) noted that when tourists have rich sensory experiences at destinations, these have a significant impact on their long-term memories of the tourism experiences, which can stimulate their positive behavioral intentions toward those destinations. Thus, we formed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7: There will be a mediating effect of tourists’ travel experience memories in the relationship between their sensory experiences and their destination loyalty.

Positive emotions felt during travels are important components of experience memories (Tung & Ritchie, 2011). Pan et al. (2016) studied the factors influencing travel experience memories and found that experiencing pleasant emotions has a significantly positive effect on the reproducibility of travel experience memories. Therefore, objects or elements that elicit numerous accompanying emotions can help people to recall memories easily and vividly (Bohanek et al., 2005). According to Cohen and Areni (1991), emotions, such as joy, felt during consumption leave strong contextual memories that can affect customer satisfaction and loyalty. Thus, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 8: Tourists’ emotions at a cultural and natural World Heritage Site will have a positive and significant impact on their travel experience memories.

Hypothesis 9: Travel experience memories will have a mediating effect in the relationship between tourists’ emotions and their loyalty.

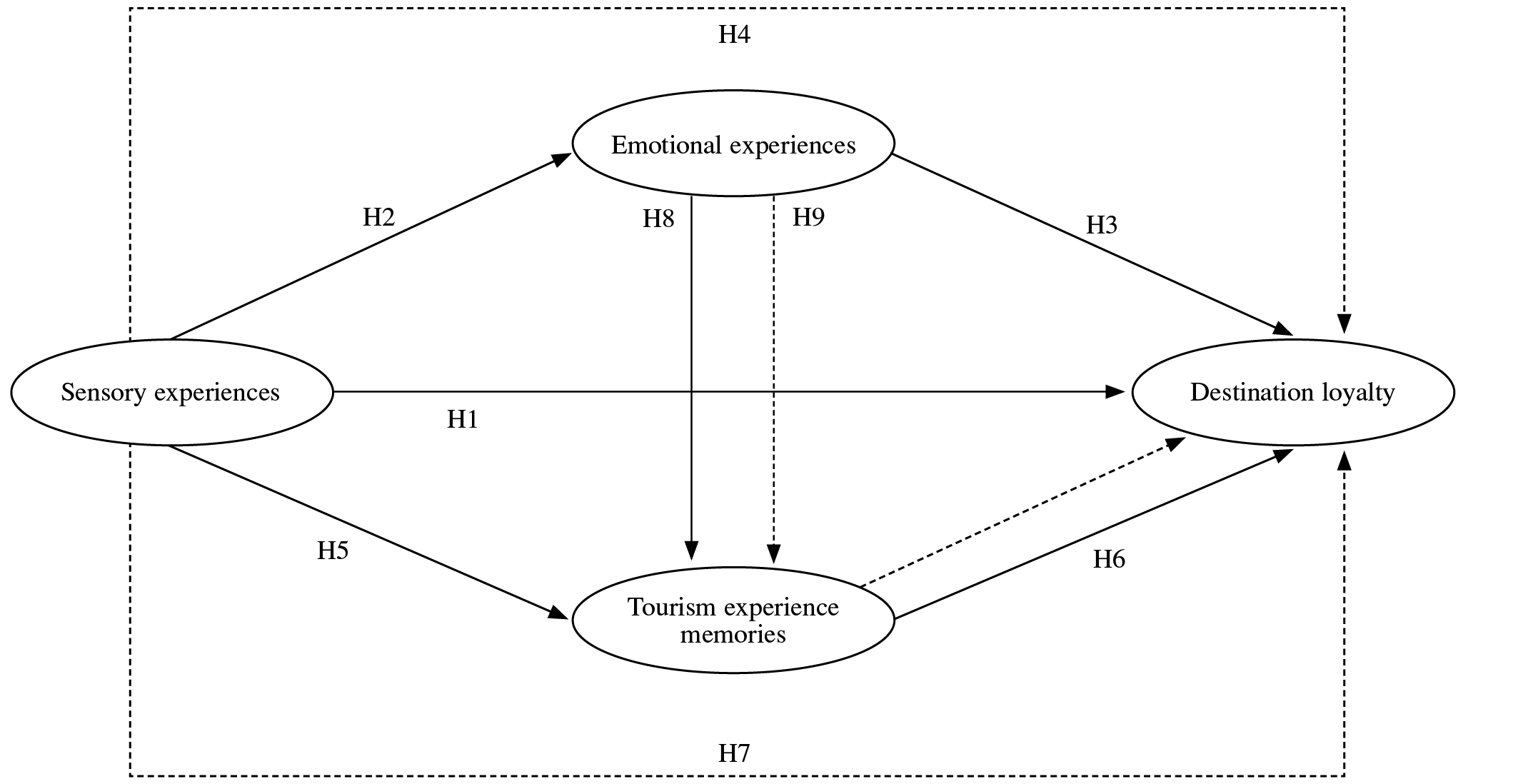

The conceptual model of how tourists’ sensory experiences relate to their emotional and sensory experiences, tourism experience memories, and loyalty to a cultural and natural World Heritage Site is expressed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research Conceptual Model

Note. Dashed lines represent mediating effects.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We conducted a survey from May to July 2020, targeting tourists above the age of 18 who traveled to Wuyi Mountain, which is a natural and cultural World Heritage Site in China. After obtaining permission from the tourists, we distributed 350 anonymous survey forms both online and on site. There were 334 tourists who returned their surveys, and 304 responses were valid (response rate = 86.9%). Among the respondents, 122 (40%) were men and 182 (60%) were women; 76 (25%) were aged between 18 and 20 years, 122 (40%) were aged between 20 and 25 years, 30 (9.9%) were aged between 26 and 30 years, 40 (13.1%) were aged between 31 and 40 years, and 36 (12%) were aged over 40 years; and 169 (52.9%) had completed high school or had an equivalent level of education, 13 (7%) held a junior college degree, 106 (34.9%) had a bachelor’s degree, and 16 (5.2%) had a graduate degree or postgraduate qualification.

Measures

The research survey consisted of two parts. The first part assessed tourists’ sensory experiences, emotions, memories of the experience, and destination loyalty, and the second part covered sociodemographic variables, including gender, age, and level of education. All the scales were sourced from the existing literature and have been validated in prior research.

The sensory experiences scale was based on the measure developed by Agapito et al. (2017) and used by Lu et al. (2019) to assess tourists’ sensory impressions. The scale comprises 18 items divided across five dimensions: vision, audition, olfaction, gustatory, and haptic. Example items are “What is your impression of the natural scenery?” and “What is your impression of the drink of tea?” Items are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (an awfully bad impression) to 7 (a particularly good impression).

Mehrabian and Russell (1974) evaluated moods or emotional states across three dimensions: pleasure, arousal, and dominance. However, marketing scholars have asserted that the two dimensions of pleasure and arousal are sufficient to represent customers’ emotional responses when shopping. Therefore, to measure tourists’ emotions we employed the two dimensions of pleasure and activation (arousal) in the Chinese version (Liu et al., 2010) of the emotion scale developed by Mehrabian and Russell. Respondents evaluate their emotional state by rating four pairs of adjectives with opposite meanings. Degree of pleasure includes happy/unhappy, troubled/untroubled, unsatisfied/satisfied, and melancholic/cheerful. Degree of activation includes inactive/hyperactive, calm/excited, sleepy/alert, and indifferent/passionate. Responses are made on a 7-point semantic difference scale ranging from 1 (the most negative emotion) to 7 (the most positive emotion).

We drew on the measurement scale of travel experience memories developed by Pan et al. (2016) and divided travel experience memories into two dimensions: reproducibility and vividness. The reproducibility items are “I can reproduce my last vacation in my mind,” “I can remember the process of my last vacation,” and “I can recall the activities I participated in during my last vacation.” The vividness items are “I can still recall my emotional feelings (happiness and/or pain) during my last vacation,” “I can also recall the layout of the main attractions during my last vacation,” and “I can still recall the main attractions I saw in my last vacation.”

The measures of tourists’ loyalty were adopted from Bonn et al. (2007) and H. Chen and Rahman (2018). One college English teacher helped to translate the six items into Chinese. The final loyalty measure we used included three items each to assess intention to recommend and revisit intention. A sample item for intention to recommend is “I will recommend this place to my friends.” A sample item for revisit intention is “I would revisit this place in the future.” Items were rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Results

Common Method Bias

We used Harman’s single-factor test to check for common method variance, and all the observed variables were included in the exploratory factor analysis. The first principal component obtained without rotation was 48.85%, which is less than the critical value of 50%, showing that there is no serious common method bias in the sample data, and that the data have good reliability.

Reliability and Validity Tests, Confirmatory Factor Analysis, and Correlation Analysis

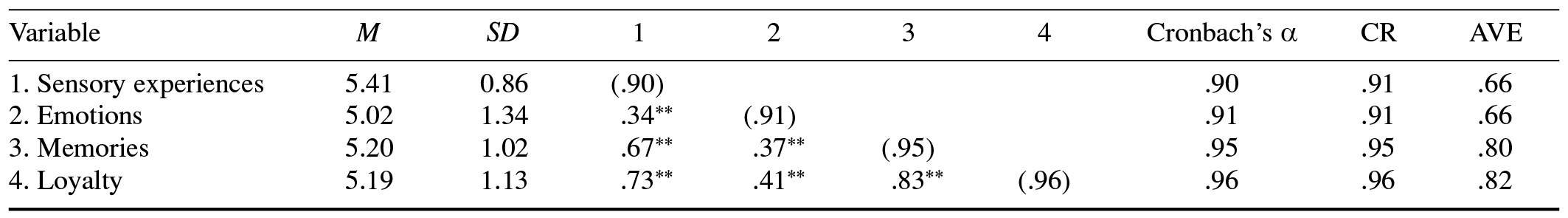

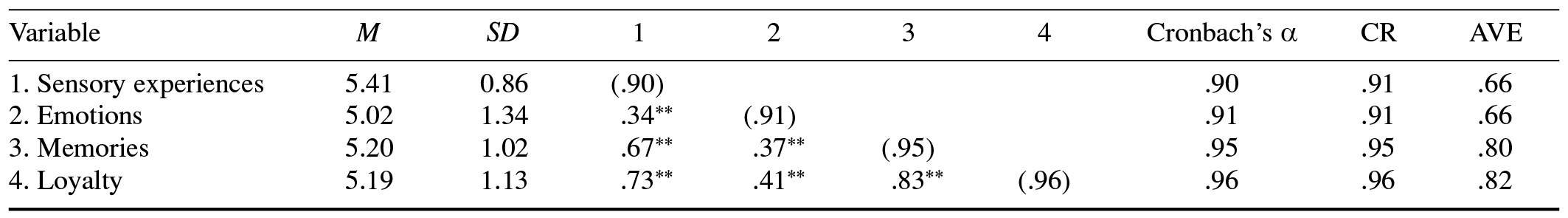

We used SPSS 24.0 to test the reliability and validity of the survey items. In the reliability analysis we used Cronbach’s alpha (> .70) as the test index, and for the validity test we used the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value (> .70) and factor loading coefficient (> .50) as the test indices. The test results show that the overall alpha coefficient of the survey items was .97, and the Cronbach’s alpha values of each dimension ranged between .90 and .96 (see Table 1), which are all greater than .70, thereby indicating that the survey items demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency. The validity test results indicate that the KMO values were as follows: sensory experience = .96, emotional experience = .89, travel experience memory = .91, tourist loyalty = .90. The factor loadings of the observed variables in each dimension were all greater than .50, indicating that the survey exhibited satisfactory validity.

We employed Amos 24.0 to perform a confirmatory factor analysis of the items in the survey. The results show (see Table 1) that the overall average variation of the average variance extracted (AVE) was greater than .60; thus, the structural validity of the survey variables was satisfactory. Further, results set out in Table 1 show that the alpha value of the survey was close to the combined validity composite reliability (CR), thereby indicating that the survey had good internal consistency reliability.

In addition, we determined that the dimensional structure of the basic model demonstrated acceptable discriminant validity by verifying the square root of the AVE and constructing a competitive model. According to the results set out in Table 1, the square root of the AVE was greater than the correlation coefficient between the variables; thus, the discriminant validity of each variable was satisfactory.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Coefficients for Study Variables

Note. CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted. Values shown in parentheses on the diagonal are Cronbach’s alphas.

** p < .01.

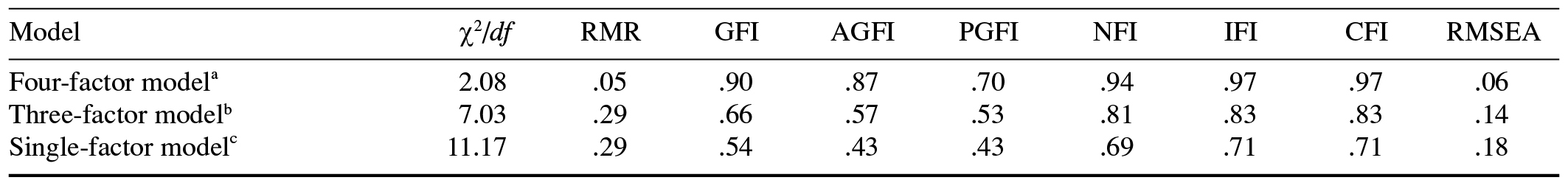

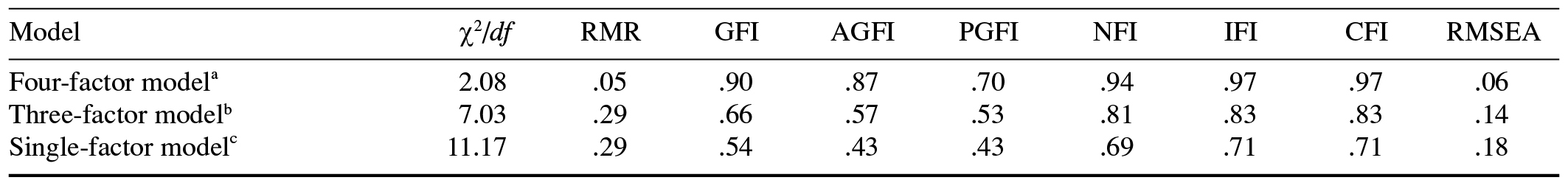

We further constructed and tested two alternative models based on the four-factor model and adopted the fit indices of chi square (χ2), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and normed fit index (NFI) to establish the fit of the model (see Table 2). For the alternative three-factor model we combined emotional experiences and travel experience memories into one factor, and for the single-factor model we combined all the variables into one factor. The verification results were based on a comparison of the fit indices of the three models. The four-factor model had a better fit to the data than did either of the other two models. Therefore, the uniqueness of the four-factor model in this study was well supported and this model could be used for the hypothesis tests.

Table 2. Competing Model Fit Indices

Note. RMR = root mean square residual; GFI = goodness-of-fit index; AGFI = adjusted goodness-of-fit index; PGFI = parsimonious goodness-of-fit index; NFI = normed fit index; IFI = incremental fit index; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

a Sensory experiences, Emotions, Memories, Loyalty

b Sensory experiences, Emotions + Memories, Loyalty

c Sensory experiences + Emotions + Memories + Loyalty

Direct Effects Test

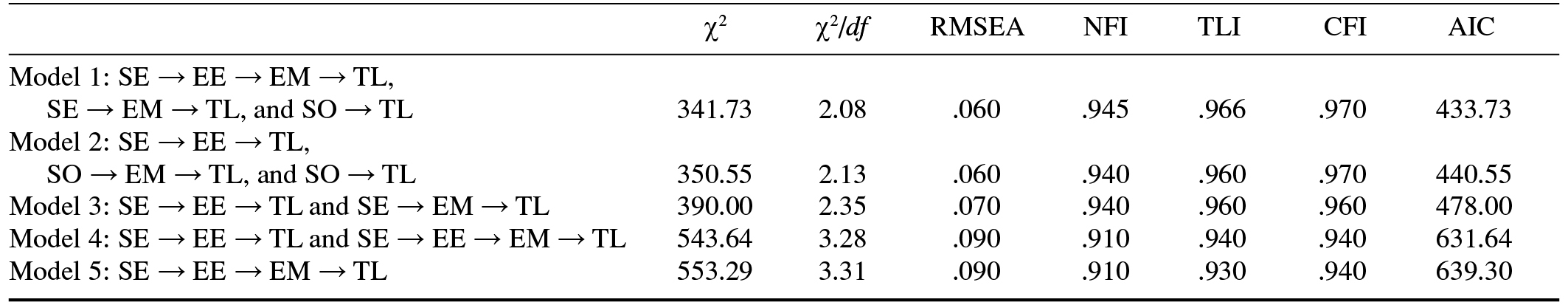

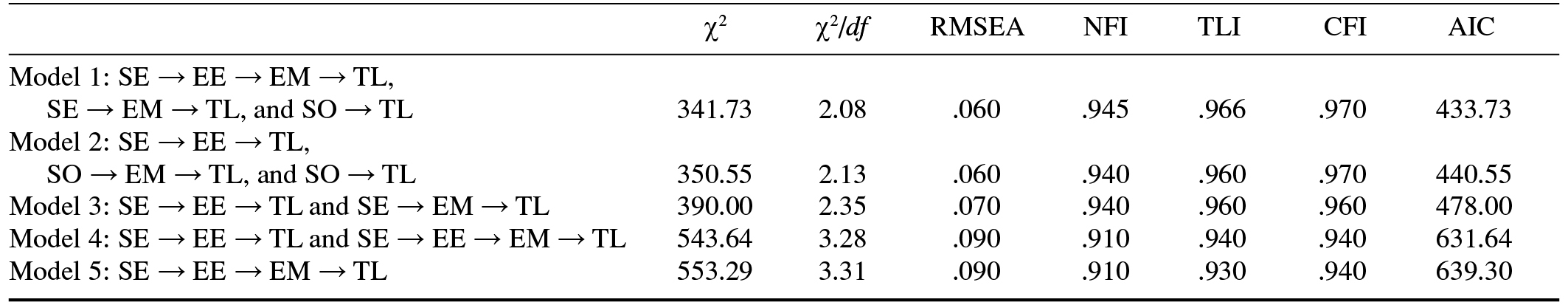

We constructed a structural equation model to analyze the influence of sensory experiences on loyalty, and to examine the roles of emotional experiences and travel experience memories. The five structural models presented in Table 3 are nested models. According to the chi-square values, we determined that Models 2, 3, 4, and 5 differed significantly from Model 1, and Model 1 had the best fit of the five models. Therefore, Model 1 was accepted.

Table 3. Structural Model Fit Indices

Note. SE = sensory experiences; EE = emotional experiences; EM = experience memories; TL = tourist loyalty; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; NFI = normed fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; CFI = comparative fit index; AIC = Akaike information criterion.

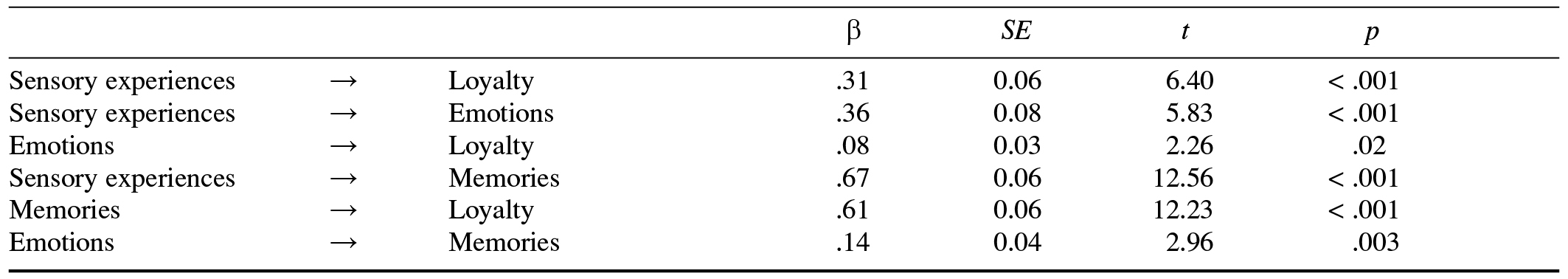

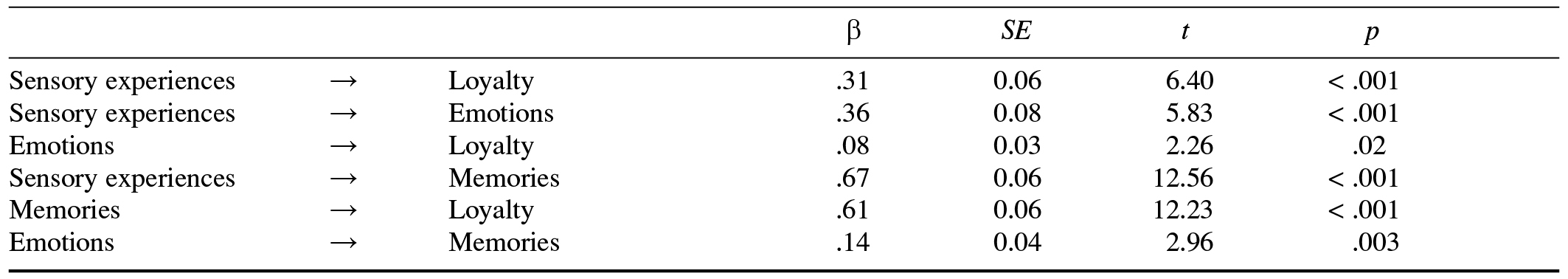

The path coefficients of Model 1 are shown in Table 4, and we compared them with the hypotheses of this research.

Table 4. Results of Direct Effect Regression Analysis

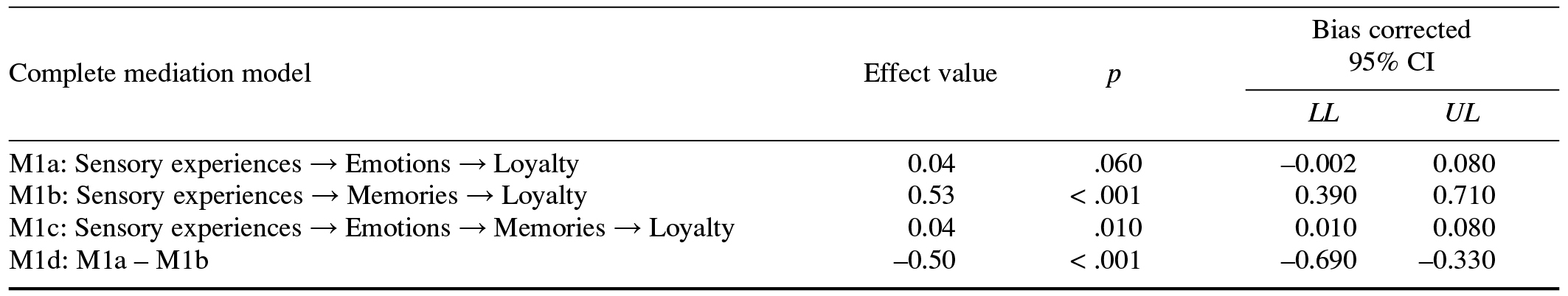

Mediating Effects Test

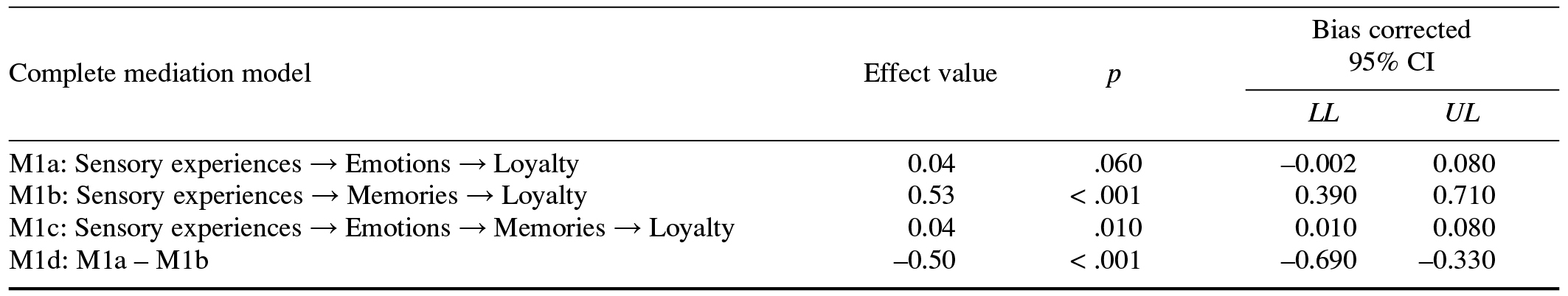

We used bootstrapping analysis to establish the significance of the mediation effects. The multiple mediation effects in this study were the individual and continuous mediation effects of emotional experiences and travel experience memories; specific mediation effects are identified as M1a, M1b, M1c, and M1d (see Table 5). We used deviation-corrected nonparametric percentiles to set the bootstrapping analysis to 5,000 runs to test the level of significance of the mediating effects. Results show that the path for the specific mediating effect of emotional experiences (M1a) between sensory experiences and loyalty was not statistically significant, that is, Hypothesis 4 was not supported. However, Hypothesis 7 (M1b) and Hypothesis 9 (M1c) were supported (see Table 5).

Table 5. Bootstrapping Analysis Results for the Mediation Model

Note. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

Discussion

We designed this study to determine the internal mechanisms by which tourists’ sensory experiences affect their loyalty to a cultural and natural World Heritage Site. Our findings indicate that the sensory experiences of tourists affected their loyalty by three internal mechanisms: First, their sensory experiences at the World Heritage Site had a direct and significant impact on their loyalty. This finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted in a coffeehouse context (H. T. Chen & Lin, 2018). Rich and attractive sensory stimulations provide tourists with good sensory experiences, which directly impact on their willingness to recommend and revisit the destination. Second, the sensory experiences of tourists positively affected their loyalty by affecting their memories of the tourism experience. This finding is also consistent with those reported in previous literature (Agapito et al., 2017). Sensory experiences produce memories, and the more reproducible and vivid these memories appear after traveling, the more likely they are to promote tourists’ loyalty to the destination. Third, the influencing path of sensory experiences emotional experiences

travel experience memories

tourist loyalty was supported by the data. This is a new finding of this study, in the context of a cultural and natural World Heritage Site; tourists obtain sensory experiences by interacting with the environment through different senses, which, in turn, affects their emotions (Krishna, 2012). The emotions induced have a significant positive effect on tourists’ memories of their visit, which can help them recall tourism experiences easily and vividly (Bohanek et al., 2005; Pan et al., 2016), and these memories further promote tourists’ loyalty toward the destination (Oh et al., 2007; Quadri-Felitti & Fiore, 2012).

Our hypothesis that tourists’ emotions would have a mediating effect in the relationship between their sensory experiences and loyalty to a World Heritage Site was not supported by the data, which conflicts with results from previous research conducted in other consumption contexts (H. T. Chen & Lin, 2018; Yüksel, 2007). This difference could be attributable to the environmental characteristics of World Heritage Sites as compared with other consumption contexts, because the natural and cultural environment of the selected case study site provides tourists with emotions of peace and calm, and these emotions did not play an obvious role between sensory experiences and destination loyalty. This emotional reaction to the site is shown in the data relating to emotion, in that most participants chose the medium point of 4 or 5 for the items on the 7-point scale. For example, for the first item of the emotion scale, 79% of participants chose scored either 4 or 5.

Our findings provide practical implications for improving the quality of tourists’ experiences and their loyalty toward destinations. First, we found that sensory experiences directly promote tourists’ loyalty toward a destination. This indicates that staff at a tourism destination should strengthen the richness and depth of tourist sensory experiences in their creation of destination tourism products, atmosphere, and marketing. Second, tourism destination managers should pay attention to the physiological and psychological mechanisms behind tourists’ sensory experiences. Tourist destinations should provide sensory experiences that can promote tourists’ cognition and emotions to strengthen their specific situational memories after a vacation, thereby affecting their decision making and behavior preferences.

Furthermore, the results for our case study World Heritage Site show that nature itself (e.g., fresh air, plants, animals, mountains, rivers) can provide comfortable and satisfying sensory experiences for tourists, and this is consistent with other researchers’ recommendations that as the physical aesthetic value of nature-based tourism increases market competitivity, destination managers should protect landscapes with good aesthetic quality from being damaged (Zhang & Xu, 2020). Thus, nature preservation is a good way to enhance tourists’ experiences and destination loyalty. For example, we conducted interviews in the scenic area of Wuyi Mountain after the survey, and tourists gave descriptions such as, “Nature and culture coexist harmoniously and jointly provide tourists with a poetic and pictorial experience” and “Opening the doors and windows in the morning is just like being in a fairyland surrounded by clouds, fragrant flowers, birds, and clear mountain air. There is no rush and bustle of the city; life here is just quiet and simple. Maybe this is the life that you and I yearn for.” As a World Heritage Site, Wuyi Mountain is rich in both natural and cultural resources. Therefore, in terms of tourism, local people and managers of the site should protect and make full use of the natural and cultural resources to fully stimulate tourists’ various senses and the synergy or complementarity among the different sensory feelings (Poon & Grohmann, 2014), to enhance tourists’ sensory and other experiences.

The main limitation in this study is that we tested tourists’ sensory experiences as a whole in the context of a World Heritage Site with both cultural and natural qualities. In previous research it has been suggested that sensory stimuli each have different and unique internal relationships with emotions, memories, cognition, and behaviors (H.-T. Chen & Lin, 2018). Stimuli obtained from each of the five senses at a cultural and natural World Heritage Site may have their own specialties. Thus, future researchers could further examine the specific characteristics of the five types of sensory experience and the different influence paths of these experience types in the context of a cultural and natural World Heritage Site.

References

Agapito, D., Mendes, J., & Valle, P. (2013). Conceptualizing the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(2), 62–73.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.03.001

Agapito, D., Pinto, P., & Mendes, J. (2017). Tourists’ memories, sensory impressions and loyalty: In loco and post-visit study in Southwest Portugal. Tourism Management, 58, 108–118.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.015

Ali, F., Kim, W. G., Li, J., & Jeon, H.-M. (2018). Make it delightful: Customers’ experience, satisfaction and loyalty in Malaysian theme parks. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 7, 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.05.003

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Sutherland, L. A. (2011). Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism: Implications for the design of powerful interpretative experiences. Tourism Management, 34(2), 770–779.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.012

Barsalou, L. W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(4), 577–660.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X99002149

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617–645.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639

Bohanek, J. G., Fivush, R., & Walker, E. (2005). Memories of positive and negative emotional events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19(1), 51–66.

https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1064

Bonn, M. A., Joseph-Mathews, S. M., Dai, M., Hayes, S., & Cave, J. B. J. (2007). Heritage/cultural attraction atmospherics: Creating the right environment for the heritage/cultural visitor. Journal of Travel Research, 45(3), 345–354.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506295947

Chen, C.-F., & Chen, F.-S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.008

Chen, H., & Rahman, I. (2018). Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 153–163.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.006

Chen, H.-T., & Lin, Y.-T. (2018). A study of the relationships among sensory experience, emotion, and buying behavior in coffeehouse chains. Service Business, 12(3), 551–573.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-017-0354-5

Chen, J. S., & Gursoy, D. (2001). An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13(2), 79–85.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110110381870

Chi, C. G.-Q., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29(4), 624–636.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

Cohen, J. B., & Areni, C. S. (1991). Affect and consumer behavior. In T. S. Robertson & H. Kassarjian (Eds.), Handbook of consumer behavior (pp. 188–240). Prentice Hall.

Davitz, J. R. (1969). The language of emotion. Academic Press.

Dolcos, F., & Cabeza, R. (2002). Event-related potentials of emotional memory: Encoding pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral pictures. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 2(3), 252–263.

https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.2.3.252

Feng, Z. L. (2010). Educational psychology. People’s Education Press.

Gentile, C., Spiller, N., & Noci, G. (2007). How to sustain the customer experience:: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), 395–410.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007.08.005

Goldstein, E. B. (2010). Sensation and perception (8th ed.). Wadsworth.

Heide, M., & Grønhaug, K. (2006). Atmosphere: Conceptual issues and implications for hospitality management. Scandinavian Journal for Hospitality and Tourism, 6(4), 271–286.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250600979515

Hicks, J. M., Page, T. J., Behe, B. K., Dennis, J. H., & Fernandez, R. T. (2005). Delighted consumers buy again. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction, and Complaining Behavior, 18, 94–104. https://bit.ly/3sZltvK

Hosany, S., & Witham, M. (2010). Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 351–364.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509346859

Kim, J.-H., Ritchie, J. R. B., & McCormick, B. (2010). Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 51(1), 12–25.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510385467

Kim, M., Vogt, C. A., & Knutson, B. J. (2013). Relationships among customer satisfaction, delight, and loyalty in the hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 39(2), 170–197.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1096348012471376

Kirillova, K., Fu, X., Lehto, X., & Cai, L. (2014). What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tourism Management, 42, 282–293.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.006

Knutson, B. J., Beck, J. A., Kim, S., & Cha, J. (2010). Service quality as a component of the hospitality experience: Proposal of a conceptual model and framework for research. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 1(13), 15–23.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15378021003595889

Krishna, A. (2012). An integrative review of sensory marketing: Engaging the senses to affect perception, judgment and behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 3(22), 332–351.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.08.003

Krishna, A. (2013). Customer sense: How the 5 senses influence buying behavior. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lin, J.-S. C., & Liang, H.-Y. (2011). The influence of service environments on customer emotion and service outcomes. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 21(4), 350–372.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521111146243

Liu, L., Tran, T., Park, K., & Wu, H. (2010). Study on the impact mechanism of perceived shopping environment on tourist shopping behavior: The mediating role of tourist shopping mood [In Chinese]. Tourism Tribune, 25(4), 55–60. https://bit.ly/3t1Xc86

Lu, X., Li, C., & Li, H. (2019). Sensory impression: An incremental explaining variable to tourist loyalty [In Chinese]. Tourism Tribune, 34(10), 47–59.

https://doi.org/10.19765/j.cnki.1002-5006.2019.10.009

Mattila, A. S., & Enz, C. A. (2002). The role of emotions in service encounters. Journal of Service Research, 4(4), 268–277.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670502004004004

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Mehraliyev, F., Kirilenko, A. P., & Choi, Y. (2020). From measurement scale to sentiment scale: Examining the effect of sensory experiences on online review rating behavior. Tourism Management, 79, Article 104096.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104096

Niedenthal, P. M, B., Barsalou, L. W., Winkielman, P., Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2005). Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 184–211.

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_1

Oh, H., Fiore, A. M., & Jeoung, M. (2007). Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 119–132.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0047287507304039

Oliver, R. L., Rust, R. T., & Varki, S. (1997). Customer delight: Foundations, findings, and managerial insight. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 311–336.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90021-X

Pan, L., Lin, B., & Wang, K. (2016). An exploration of the factors influencing tourism experience memory: A study based on tourism in China [In Chinese]. Tourism Tribune, 31(1), 49–57. https://bit.ly/2MumuuN

Pine, B. J., II, & Gilmore, J. H. (2011). The experience economy: Competing for customer time, attention, and money. Harvard Business School Press.

Poon, T., & Grohmann, B. (2014). Spatial density and ambient scent: Effects on consumer anxiety. American Journal of Business, 29(1), 76–94.

https://doi.org/10.1108/AJB-05-2013-0027

Qiu, Y., Liu, B., & Huang, Q. (2017). Functional, sensory, affective: Effect of different product experiences on customer satisfaction and loyalty [In Chinese]. Consumer Economics, 4(33), 59–67. https://bit.ly/3rggEwR

Quadri-Felitti, D., & Fiore, A. M. (2012). Experience economy constructs as a framework for understanding wine tourism. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18(1), 3–15.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1356766711432222

Richins, M. L. (1997). Measuring emotions in the consumption experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(2), 127–146.

https://doi.org/10.1086/209499

Torres, E. N., & Kline, S. F. (2006). From satisfaction to delight: A model for the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 18(4), 290–301.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110610665302

Tung, V. W. S., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2011). Investigating the memorable experiences of the senior travel market: An examination of the reminiscence bump. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(3), 331–343.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.563168

Wang, S. (2017). The application of multisensory experiences in museum exhibitions making: Theories and practices with Taizhou Museum’s People of the Sea exhibition as an example [In Chinese]. Southeast Culture, 4, 121–126.

https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-179X.2017.04.018

Xu, C., Zuo, X., Hu, T., & He, Y. (2018). Research on the relationship between tourism situation, tourist emotion and tourist loyalty—Taking Yueyang Tower-Junshan Tourist Area as an example [In Chinese]. Journal of Huaqiao University (Humanities & Social Science), 5, 41–51.

https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-1398.2018.05.005

Yüksel, A. (2007). Tourist shopping habitat: Effects on emotions, shopping value and behaviours. Tourism Management, 28(1), 58–69.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.07.017

Zhang, Q., & Xu, H. (2020). Understanding aesthetic experiences in nature-based tourism: The important role of tourists’ literary associations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, Article 100429.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100429

Agapito, D., Mendes, J., & Valle, P. (2013). Conceptualizing the sensory dimension of tourist experiences. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2(2), 62–73.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2013.03.001

Agapito, D., Pinto, P., & Mendes, J. (2017). Tourists’ memories, sensory impressions and loyalty: In loco and post-visit study in Southwest Portugal. Tourism Management, 58, 108–118.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.015

Ali, F., Kim, W. G., Li, J., & Jeon, H.-M. (2018). Make it delightful: Customers’ experience, satisfaction and loyalty in Malaysian theme parks. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 7, 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.05.003

Ballantyne, R., Packer, J., & Sutherland, L. A. (2011). Visitors’ memories of wildlife tourism: Implications for the design of powerful interpretative experiences. Tourism Management, 34(2), 770–779.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.012

Barsalou, L. W. (1999). Perceptual symbol systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22(4), 577–660.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X99002149

Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617–645.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093639

Bohanek, J. G., Fivush, R., & Walker, E. (2005). Memories of positive and negative emotional events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19(1), 51–66.

https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1064

Bonn, M. A., Joseph-Mathews, S. M., Dai, M., Hayes, S., & Cave, J. B. J. (2007). Heritage/cultural attraction atmospherics: Creating the right environment for the heritage/cultural visitor. Journal of Travel Research, 45(3), 345–354.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287506295947

Chen, C.-F., & Chen, F.-S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.008

Chen, H., & Rahman, I. (2018). Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 153–163.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.006

Chen, H.-T., & Lin, Y.-T. (2018). A study of the relationships among sensory experience, emotion, and buying behavior in coffeehouse chains. Service Business, 12(3), 551–573.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-017-0354-5

Chen, J. S., & Gursoy, D. (2001). An investigation of tourists’ destination loyalty and preferences. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13(2), 79–85.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110110381870

Chi, C. G.-Q., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29(4), 624–636.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.007

Cohen, J. B., & Areni, C. S. (1991). Affect and consumer behavior. In T. S. Robertson & H. Kassarjian (Eds.), Handbook of consumer behavior (pp. 188–240). Prentice Hall.

Davitz, J. R. (1969). The language of emotion. Academic Press.

Dolcos, F., & Cabeza, R. (2002). Event-related potentials of emotional memory: Encoding pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral pictures. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 2(3), 252–263.

https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.2.3.252

Feng, Z. L. (2010). Educational psychology. People’s Education Press.

Gentile, C., Spiller, N., & Noci, G. (2007). How to sustain the customer experience:: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal, 25(5), 395–410.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007.08.005

Goldstein, E. B. (2010). Sensation and perception (8th ed.). Wadsworth.

Heide, M., & Grønhaug, K. (2006). Atmosphere: Conceptual issues and implications for hospitality management. Scandinavian Journal for Hospitality and Tourism, 6(4), 271–286.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250600979515

Hicks, J. M., Page, T. J., Behe, B. K., Dennis, J. H., & Fernandez, R. T. (2005). Delighted consumers buy again. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction, and Complaining Behavior, 18, 94–104. https://bit.ly/3sZltvK

Hosany, S., & Witham, M. (2010). Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 351–364.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509346859

Kim, J.-H., Ritchie, J. R. B., & McCormick, B. (2010). Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research, 51(1), 12–25.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510385467

Kim, M., Vogt, C. A., & Knutson, B. J. (2013). Relationships among customer satisfaction, delight, and loyalty in the hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 39(2), 170–197.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1096348012471376

Kirillova, K., Fu, X., Lehto, X., & Cai, L. (2014). What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tourism Management, 42, 282–293.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.006

Knutson, B. J., Beck, J. A., Kim, S., & Cha, J. (2010). Service quality as a component of the hospitality experience: Proposal of a conceptual model and framework for research. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 1(13), 15–23.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15378021003595889

Krishna, A. (2012). An integrative review of sensory marketing: Engaging the senses to affect perception, judgment and behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 3(22), 332–351.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.08.003

Krishna, A. (2013). Customer sense: How the 5 senses influence buying behavior. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lin, J.-S. C., & Liang, H.-Y. (2011). The influence of service environments on customer emotion and service outcomes. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 21(4), 350–372.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521111146243

Liu, L., Tran, T., Park, K., & Wu, H. (2010). Study on the impact mechanism of perceived shopping environment on tourist shopping behavior: The mediating role of tourist shopping mood [In Chinese]. Tourism Tribune, 25(4), 55–60. https://bit.ly/3t1Xc86

Lu, X., Li, C., & Li, H. (2019). Sensory impression: An incremental explaining variable to tourist loyalty [In Chinese]. Tourism Tribune, 34(10), 47–59.

https://doi.org/10.19765/j.cnki.1002-5006.2019.10.009

Mattila, A. S., & Enz, C. A. (2002). The role of emotions in service encounters. Journal of Service Research, 4(4), 268–277.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670502004004004

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Mehraliyev, F., Kirilenko, A. P., & Choi, Y. (2020). From measurement scale to sentiment scale: Examining the effect of sensory experiences on online review rating behavior. Tourism Management, 79, Article 104096.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104096

Niedenthal, P. M, B., Barsalou, L. W., Winkielman, P., Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2005). Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 184–211.

https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_1

Oh, H., Fiore, A. M., & Jeoung, M. (2007). Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 119–132.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0047287507304039

Oliver, R. L., Rust, R. T., & Varki, S. (1997). Customer delight: Foundations, findings, and managerial insight. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 311–336.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90021-X

Pan, L., Lin, B., & Wang, K. (2016). An exploration of the factors influencing tourism experience memory: A study based on tourism in China [In Chinese]. Tourism Tribune, 31(1), 49–57. https://bit.ly/2MumuuN

Pine, B. J., II, & Gilmore, J. H. (2011). The experience economy: Competing for customer time, attention, and money. Harvard Business School Press.

Poon, T., & Grohmann, B. (2014). Spatial density and ambient scent: Effects on consumer anxiety. American Journal of Business, 29(1), 76–94.

https://doi.org/10.1108/AJB-05-2013-0027

Qiu, Y., Liu, B., & Huang, Q. (2017). Functional, sensory, affective: Effect of different product experiences on customer satisfaction and loyalty [In Chinese]. Consumer Economics, 4(33), 59–67. https://bit.ly/3rggEwR

Quadri-Felitti, D., & Fiore, A. M. (2012). Experience economy constructs as a framework for understanding wine tourism. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 18(1), 3–15.

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1356766711432222

Richins, M. L. (1997). Measuring emotions in the consumption experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(2), 127–146.

https://doi.org/10.1086/209499

Torres, E. N., & Kline, S. F. (2006). From satisfaction to delight: A model for the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 18(4), 290–301.

https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110610665302

Tung, V. W. S., & Ritchie, J. R. B. (2011). Investigating the memorable experiences of the senior travel market: An examination of the reminiscence bump. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 28(3), 331–343.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2011.563168

Wang, S. (2017). The application of multisensory experiences in museum exhibitions making: Theories and practices with Taizhou Museum’s People of the Sea exhibition as an example [In Chinese]. Southeast Culture, 4, 121–126.

https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-179X.2017.04.018

Xu, C., Zuo, X., Hu, T., & He, Y. (2018). Research on the relationship between tourism situation, tourist emotion and tourist loyalty—Taking Yueyang Tower-Junshan Tourist Area as an example [In Chinese]. Journal of Huaqiao University (Humanities & Social Science), 5, 41–51.

https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-1398.2018.05.005

Yüksel, A. (2007). Tourist shopping habitat: Effects on emotions, shopping value and behaviours. Tourism Management, 28(1), 58–69.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.07.017

Zhang, Q., & Xu, H. (2020). Understanding aesthetic experiences in nature-based tourism: The important role of tourists’ literary associations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 16, Article 100429.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100429

Figure 1. Research Conceptual Model

Note. Dashed lines represent mediating effects.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Coefficients for Study Variables

Note. CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted. Values shown in parentheses on the diagonal are Cronbach’s alphas.

** p < .01.

Table 2. Competing Model Fit Indices

Note. RMR = root mean square residual; GFI = goodness-of-fit index; AGFI = adjusted goodness-of-fit index; PGFI = parsimonious goodness-of-fit index; NFI = normed fit index; IFI = incremental fit index; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

a Sensory experiences, Emotions, Memories, Loyalty

b Sensory experiences, Emotions + Memories, Loyalty

c Sensory experiences + Emotions + Memories + Loyalty

Table 3. Structural Model Fit Indices

Note. SE = sensory experiences; EE = emotional experiences; EM = experience memories; TL = tourist loyalty; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; NFI = normed fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; CFI = comparative fit index; AIC = Akaike information criterion.

Table 4. Results of Direct Effect Regression Analysis

Table 5. Bootstrapping Analysis Results for the Mediation Model

Note. CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit.

This work was supported by the Social Science Program of the Ministry of Education of China (18YJA630039) and the Social Science Program of the Education Department of Fujian Province

China (JAS20381).

Anmin Huang, College of Tourism, Huaqiao University, Fengze District, Quanzhou City, Fujian Province 362021, People’s Republic of China. Email: [email protected]