Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale: Revised for use in both psychiatric care and social services

Main Article Content

The Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale (ConSat) is a self-rating instrument that was originally designed solely for use with clients receiving psychiatric care. Therefore, it was decided within the frame of the Swedish Quality Star National Psychiatric Register to develop a revised instrument (i.e., the ConSat–R). We investigated whether or not the ConSat–R could replace the ConSat for use for provision of both psychiatric care and social services. After pilot testing and further revisions, we tested the instrument at 2 time-points, with an interval of from 1 to 3 weeks. Participants were 53 clients (26 men, 27 women) in 11 different teams in middle and southwest Sweden. Results showed a high correlation between the ConSat and the ConSat–R and high or acceptable correlations even at the level of the items. The reliability was examined with regard to homogeneity, which showed high values for the ConSat–R. The conclusion was that the ConSat–R may be used with clients receiving both psychiatric care and social services.

There has been a general consensus reached that successful care and nursing may often be related to the provision of treatment and service in a way that the clients perceive with satisfaction (Angantyr, Rimner, Nordén, & Norlander, 2015; Helldin, Kane, Karilampi, Norlander, & Archer, 2008). Satisfaction with psychiatric care is a complex, multidimensional construct (Howard, Rayens, El-Mallakh, & Clark, 2007; Ingvarsson, Nordén, & Norlander, 2014) and in theories of client satisfaction it has been indicated that the patient construct encompasses processes and outcomes of treatment, as well as structural aspects (Ahlfors et al., 2001; Mahon, 1996; Norlander, Ernestad, Moradiani, & Nordén, 2015). Researchers have shown that central aspects of clients’ perception of satisfaction with psychiatric care are as follows: (a) their expectations of the treatment, (b) their view of the care provided, (c) the attitudes of the staff, and (d) the treatment outcome (Ivarsson, 2011; Siponen & Välimäki, 2003).

In the year 2001, a network was set up in Sweden consisting of psychiatrists and other caregivers in clinical practice, with the purpose of providing simple, nationally applicable outcome measures of the provision of psychiatric care (Erdner & Ivarsson, 2001; Ivarsson, Erdner, & Malm, 2006). A test battery was assembled and labeled the Quality Star (in Swedish: Kvalitetsstjärnan), which also became the name of the network itself. The Quality Star is a measurement system encompassing the eight dimensions of consumer satisfaction, quality of life, psychosocial functioning, burden to a significant other, resources, group-specific, symptom severity, and subjective distress. For each dimension, there are tests with items that are rated on a scale ranging from 0 to 100, where 0 means very ill and 100 means as healthy as can be. Respondents rate their consumer satisfaction, quality of life, and subjective distress, whereas their next of kin rate perceived burden, and the health care staff rate the other dimensions. By representing the Quality Star as a figure resembling a sun with eight rays, a graphic picture of the client’s situation is displayed by linking together the points on the different rays. The further out on the rays that the points are scored, the healthier is the individual client. This type of presentation was geared toward the facilitation of a dialogue with the client about his/her current situation and joint planning of continued work of improvement. That is to say, collected data would not only help build a national quality register but also simultaneously constitute a tool for the future treatment and care of the individual client.

The psychiatrists and caregivers who make up the network of the Quality Star conduct ongoing meetings with representatives from the clinics that participate in the program, at which they report on how the various measurement instruments are to be used. There are also training materials designed for use with role play to ensure that the instruments are administered in a unified way. Questions about developmental work are also dealt with at the meetings. The decision- making assembly is the Executive Committee (in Swedish: Gemensamma Genomförandegruppen), which is responsible for the coordination of the activities and with ensuring that the developmental work is conducted in an ethically correct way in accordance with the Swedish law of ethics (Gemensamma Genomförandegruppen, 2013).

Care and support for clients are developed in an increasingly integrative way in Sweden, where caregivers and psychiatrists provide treatment and service by collaborating jointly with clients. Thus, integration with social services personnel has increased in areas such as housing support and assistance in daily living. In this collaboration, social services personnel have often stated that some of the items in the Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale (ConSat; Ivarsson & Malm, 2007) excluded the opportunity for clients to express their perceived satisfaction concerning the social services being provided for them (Gemensamma Genomförandegruppen, 2013). In Sweden, the administration of psychiatric care services is performed by regional county councils, whereas local municipalities are responsible for provision of social services. Against this background, the Quality Star Executive Committee decided to investigate the possibilities for changing the self-rating ConSat from being designed solely for use with clients receiving psychiatric care to a revised instrument (i.e., the ConSat–R) that could be used for assessing the quality of both psychiatric care and social services. The ConSat was already a revised version of the Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale, originally developed by the Committee for Clinical Trials (in Swedish, Udvalg for Kliniske Undersøgelser, UKU) within the Scandinavian Society for Psychopharmacology (UKU-ConSat; Ahlfors et al., 2001). The critical difference between the UKU-ConSat and the ConSat was that the original instrument was not based on the self-ratings of the client but was assessed by staff on the basis of their observations and interviews.

Purpose

Our purpose was to investigate whether or not the ConSat–R could replace the ConSat to enable the use of this instrument within the provision of both psychiatric care and social services.

Method

Participants

Participants were 53 clients (26 men, 27 women) with an average age of 40.36 years (SD = 12.82). The psychiatrists and caregivers working in the network for the Swedish register of the Quality Star recruited the participants from 11 different teams in middle and southwest Sweden, where 11 of the participants had their chief contact with psychiatric care through the regional county council, and 26 of the participants had their main contact with social services provided by the local municipality. There were also 15 clients who had equal contact with both the regional and local authorities. Of the clients, 28 (52.8%) had been diagnosed with various types of psychosis, 25 (47.2%) had been diagnosed as having other forms of severe mental illness (SMI). As part of the study procedure, we also used the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF; American Psychiatric Association, 2002; Pedersen, Hagtvet, & Karterud, 2007) on two occasions of data collection to assess and control for similarity of level of functioning of the participants at each of those time points. On the first occasion, the mean for GAF symptoms was 52.9 (SD = 12.44) and the mean for GAF functioning was 51.9 (SD = 12.07), indicating symptoms and functional difficulties ranging from serious to moderate. There was no significant change in those levels on the second occasion of data collection.

Instruments

Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale (ConSat). The ConSat was originally developed in Swedish. It has been shown to have good psychometric characteristics, and has been validated for use with people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, affective disorders, anxiety, and substance abuse syndromes (Ivarsson & Malm, 2007). The characteristics of the ConSat as a well-functioning, clinical instrument have been confirmed in a number of Swedish studies (e.g., Ivarsson, Lindström, Malm, & Norlander, 2011a, 2011b; Ivarsson, Malm, Lindström, & Norlander, 2010; Nordén, Ivarsson, Malm, & Norlander, 2011). The instrument consists of 11 items within the following domains: availability, atmosphere, continuity, information and participation, drug treatment, psychological and psychosocial interventions, results of treatment/care, and trust in future well-being. Except for item 8a—in which the client confirms whether or not he or she is receiving medication, and where there is a selection variable of item 8b or item 8c depending on response to item 8a—all items are rated on a 7-point scale with the format: +3 = full satisfaction, +2 = satisfied but with minor dissatisfaction, +1 = more satisfaction than dissatisfaction, 0 = equal satisfaction/ dissatisfaction or indecisive, and ratings from -1 to -3 are formatted in the same way for responses where clients indicate their dissatisfaction is greater than their satisfaction. The total score, thus, ranges from -33 to +33. Total raw scores are transformed into percentages, where 0% indicates extreme dissatisfaction and 100% indicates complete satisfaction.

The initial introductory instruction is as follows: “In the following questionnaire, we would like you to tell us how you have experienced the service you received.” This is followed by the instruction: “Please circle the alternative that most accurately describes how you have experienced the situation described.” The instrument is not presented to the clients with the numbers (-3 to +3) but with obvious verbal anchor points such as “Very poor–Very good,” “Very negatively–Very positively,” and “Very little–Very much.” Between the two anchor points are matching descriptions of the various scale steps, as shown in the following example: “Very poor” (-3), “Poor” (-2), “Fairly poor” (-1), “Neither good nor bad (indecisive)” (0), “Fairly good” (1), “Good” (2), and “Very good” (3).

Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale, revised version (ConSat–R). The Executive Committee of the Quality Star appointed a working group consisting of 14 individuals, all of whom had significant experience in psychiatric care and social services, respectively, and who were assigned the task of constructing a revised version of the ConSat to enable the use of the instrument within both psychiatric care and social services in line with the work approach of the Resource Group Assertive Community Treatment (Andersson, Ivarsson, Tungström, Malm, & Norlander, 2014; Nordén, Malm, & Norlander, 2012). Six of the members of the working group were employed by county councils, six were employed by municipal councils, and two were in private practice. By profession, they were nurses, project leaders, psychiatrists, and managers. A series of working meetings was organized with the purpose of developing a consensus-based generic version of the instrument. Formulations in the ConSat were scrutinized in order to identify any wording of items that might be difficult for the clients to understand. At the same time, the group members were careful not to make any changes that might alter the fundamental content of an item. Furthermore, the original anchor points, and the designations of steps on the scale were retained.

The next step in the development of the revised version of the ConSat was to test its comprehensibility with the intended users. In collaboration with the managers, the Executive Committee from the five professional domains decided to test the comprehensibility of the instrument as part of routine quality testing performed at the clinics. The collaborating managers gave permission for this procedure to be carried out, and these managers were also responsible for verifying that the researchers followed the ethical standards of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki concerning the ethical principles of medical research involving human subjects (World Medical Association, 2008). The clients who were asked if they would participate were given oral and written information about the test. They were told that they had the right to discontinue participation at any time without providing a reason, and that participation would not in any way affect their ongoing treatment or support. Furthermore, all information the clients provided would have any personal details by which they could be identified removed. The participants were 21 clients (four men, 17 women) with a mean age of 45.8 years (SD = 12.6). Of the clients, seven were receiving psychiatric care through a county council, and 11 were recipients of social services provided by municipal authorities. Among the participants, there were 14 who had no previous experience with use of the ConSat. The seven participants who had previously rated their services and care on the ConSat, had done so at least 4 months before taking part in the tests conducted for this study. With regard to their mental state, 16 clients had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, and three had been diagnosed with affective psychoses as well as occasional attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and fleeting states of psychosis.

The rating procedure used for the test was as follows: The first request that the case manager made of the client was “Please, read the questions and see if you can respond to them,” The case manager then asked the client: “Is anything unclear so that you don’t know what to answer?” The case manager then noted if the client understood right away or if explanations were needed, and in some specific cases, if the case manager was doubtful about whether or not the client had understood, this was noted, or if an explanation was necessary the case manager noted what had to be explained. The case manager then proceeded to ask the questions that make up the revised version of the ConSat, and recorded the answers that the client gave.

After the completed questionnaires had been processed to remove any personal details that could identify the individual clients, the responses were then analyzed by three members of the working group that had developed the revised version of the ConSat. That work led to the improvement of a few of the items in the revised version. The modified instrument was then presented to the Executive Committee, who confirmed that the revised version (i.e., the ConSat–R, see Table 2) could be used for the purpose of validating this scale against the original scale and who also decided that the revised version would be made available to the Quality Star network. Psychometric studies could then be conducted.

In all the steps described above, the original Swedish version of the ConSat was used and all successive alterations, resulting in the ConSat–R, were also made in Swedish. The ConSat–R was translated into English for the present study by a professional translator who specializes in the fields of medicine and psychology. The items in the ConSat–R are set out in Table 1.

Table 1. Items for Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale – Revised (ConSat–R) With Anchor Points (Low, High)

Procedure

When the revision of the ConSat was completed, the Executive Committee of the Quality Star decided to continue the work of improving the quality of the Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale through the use of both the ConSat and the ConSat–R, as part of their ordinary activity, with the ongoing collections of information of client satisfaction that was carried out with their treatment. At this point, 11 clinics and caregiving agencies expressed an interest in taking part in the study. The managers of the collaborating units were responsible for the fact that the researchers followed the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration, and that the clients who were approached about participation were given information about the test and informed that they had the right to discontinue participation without providing a reason at any time, and that their participation would not in any way affect their ongoing treatment or support. Furthermore, the clients were assured that any personal details would be removed from all collected material so that they could not be individually identified and that complete anonymity would be assured should the information be published.

The data collection took place on two occasions with an interval of 1 to 3 weeks (M = 14.76 days, SD = 9.43) and to avoid results being influenced by order of presentation, the questionnaire forms were distributed randomly, so that on the first occasion approximately half of the participants rated their degree of satisfaction using the ConSat, whereas the other half of the participants completed the ConSat–R. For background data, participants completed the GAF Scale on both testing occasions. The Executive Committee of the Quality Star decided that the collected, anonymized material should be accessible to the network of psychiatrists and caregivers on the quality register in order to enable statistical descriptions and reports to be prepared, but the material was analyzed only when the current study was completed. Before submission of the manuscript to a scientific journal, it was scrutinized by the Ethical Committee at Evidens University College, whose members came to the conclusion that the content conformed to Swedish law and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Comparing Means

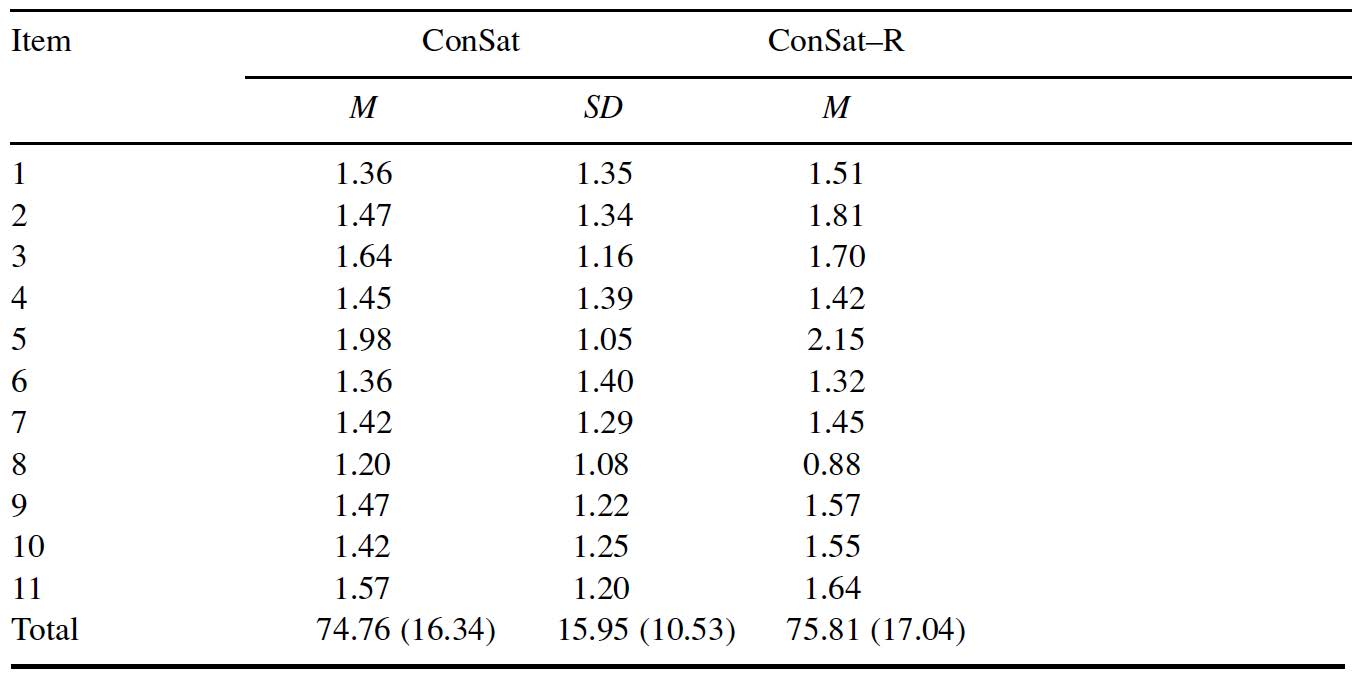

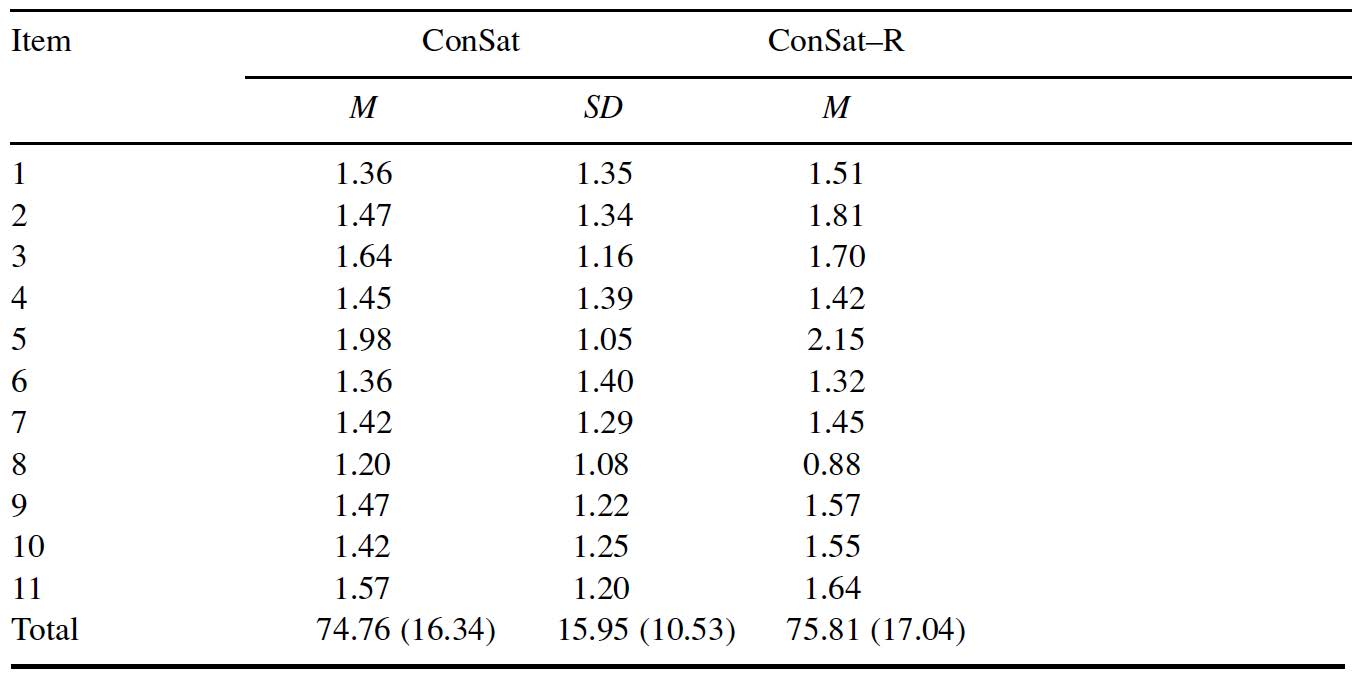

A paired samples t test (5% level) was conducted to establish whether or not there were any significant differences between the ConSat and the ConSat–R. The results showed no differences between the ratings of the participants on the two instruments (p = .359). In Table 2, means and standard deviations are given for raw scores on the 11 items in each scale, and the total values for the ConSat and the ConSat–R are given on a scale from 0 to 100, with the raw scores within parentheses.

Table 2. Means and Standard Deviations in Raw Scores for Items

Correlations

Results of a correlational analysis (Spearman’s rho, 5% level) with the total sum for ConSat and each of the 11 items showed high correlations with regard to the total sum (range: .70–.88). Corresponding results were obtained in yet another analysis where the total sum for the ConSat–R was correlated with the revised items (range: .52–.88).

Validity

One purpose in the current study was to examine whether or not the ConSat–R could be validated in relation to the original ConSat. Analyses were conducted with the help of Spearman’s rho (5% level). The results showed a high correlation between the ConSat and the ConSat–R, and high or acceptable correlations even at the level of the individual items (see Table 3).

Table 3. Correlations (Spearman’s rho) in Regard to Items and Total Scores

Reliability

The homogeneity of the ConSat and the ConSat–R was examined by calculation of Cronbach’s alpha (5% level) and the Guttman split-half coefficient (5% level). The results of calculation of Cronbach’s alpha showed high coefficients for both the ConSat (.93) and the ConSat–R (.91). The results of calculation of the Guttman split-half coefficient also showed high values for the ConSat (.89) and the ConSat–R (.81). There was no significant difference (independent samples t test, 5% level) between the ratings of the clients with regard to either the ConSat or the ConSat–R, as presented by case managers employed by the municipal authorities (29 assessments) or by the case managers employed by the regional authorities (24 assessments), or between those who completed the ConSat on the first testing occasion (33 clients) compared to those (20 clients) who completed the ConSat–R on the first testing occasion (ps > .05). A continued analysis also did not show any significant differences with regard to the gender of the clients or their diagnoses for either the ConSat or the ConSat–R (ps > .05).

Discussion

We sought to examine whether or not the ConSat–R could replace the ConSat as a measure for use within both the provision of psychiatric care (administered by county councils) and the provision of social services (administered by municipal authorities). The results showed that the ConSat–R has sufficiently good psychometric properties to be able to replace the ConSat in these contexts, although this conclusion should be limited to clients diagnosed with SMI in their support and rehabilitation phases.

Concurrent validity was tested by having a group of clients complete the ConSat and the ConSat–R on two occasions, and the results showed a high correlation between the ConSat and the ConSat–R, and high or acceptable correlations even at the item level. The validity was further underscored by the fact that, by comparing means between the items and according to the correlations between each total test sum and the individual items, it was found that both versions of the test had comparable structures. The reliability was examined with regard to homogeneity, which showed high and highly similar values for both the ConSat and the ConSat–R. In this context, a strength was that there was no observable effect of the order in which the clients completed the tests and we also found that whether the tests were presented by case managers employed by the municipalities or by the county councils did not have any effect. We were also able to conclude that neither the gender of the clients nor the illness that they had been diagnosed with, in terms of psychoses compared to diagnosis of another type of mental disorder, affected the results.

The current investigation did, however, have some limitations. As can be seen in the results presented in Table 3, the data collected for this research were collected primarily from users with a relatively high degree of satisfaction as measured by the ConSat and the ConSat–R. For this reason, it is a weakness that possible differences among clients with pronounced dissatisfaction could not be analyzed. Furthermore, future studies ought to be conducted with a number of clients sufficient for the effects of the instrument to be examined relative to a wider range of diagnoses of mental illness (e.g., drug abuse, personality disorders, and affective states).

Nevertheless, despite these shortcomings, we have shown that the ConSat–R can be used within the provision of both psychiatric care and social services, and our findings may also serve as the foundation for future studies. In addition, it has recently come to the attention of the authors that some of the clinics in the Quality Star network have begun to use the ConSat–R on a trial basis as part of their regular activities, and have already reported good experiences.

References

Ahlfors, U. G., Lewander, T., Lindström, E., Malt, U. F., Lublin, H., & Malm, U. (2001). Assessment of patient satisfaction with psychiatric care. Development and clinical evaluation of a brief consumer satisfaction scale (UKU-ConSat). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 55, 71–90. http://doi.org/bwk6pz

American Psychiatric Association. (2002). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.: DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: Author.

Andersson, J., Ivarsson, B., Tungström, S., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2014). The Clinical Strategies Implementation Scale revised (CSI-R). Fidelity assessment of Resource Group Assertive Community Treatment. Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 3, 36–41. http://doi.org/9th

Angantyr, K., Rimner, A., Nordén, T., & Norlander, T. (2015). Primary care behavioral health model: Perspectives of outcome, client satisfaction, and gender. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 43, 287–301. http://doi.org/9tj

Erdner, L., & Ivarsson, B. (2001). The Quality Star – A tool for regular outcome monitoring [Monograph]. In M. London (Ed.), ENTER conference monographs, London 2000, Paris 2001 (pp. 65–69). Cambridge: Print Out.

Gemensamma Genomförandegruppen. (2013). Rapport för år 2012. Förslag till fortsatta aktiviteter år 2013 [Report from 2012. Suggestions for future activities for the year 2013]. Kungälv: Kvalitetsstjärnan. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/27SSvxH

Helldin, L., Kane, J., Karilampi, U., Norlander, T., & Archer, T. (2008). Experience of quality of life and attitude to care and treatment in patients with chronic schizophrenia: Role of cross-sectional remission. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 12, 97–104. http://doi.org/d4h8f8

Howard, P. B., Rayens, M. K., El-Mallakh, P., & Clark J. J. (2007). Predictors of satisfaction among adult recipients of medicaid mental health services. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 21, 257–269. http://doi.org/bh3bv7

Ingvarsson, T., Nordén, T., & Norlander, T. (2014). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: A case study on experiences of healthy behaviors by clients in psychiatric care. Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 3, 390–402. http://doi.org/9v6

Ivarsson, B. (2011). Tools for outcome-informed management of mental illness: Psychometric properties of instruments of the Swedish clinical multicenter Quality Star cohort (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Karlstad University, Sweden.

Ivarsson, B., Erdner, L., & Malm, U. (2006, June). The Quality Star—An algorithm for the evaluation of mental health services. Presentation for ENMESH conference, Lund, Sweden (Vol. 10). Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1HVd1UU

Ivarsson, B., Lindström, L., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2011a). Consumer satisfaction, quality of life and distress with regard to social function and gender in severe mental illness. Open Journal of Psychiatry, 1, 88–97. http://doi.org/ffqkt9

Ivarsson, B., Lindström, L., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2011b). The self-assessment of Perceived Global Distress Scale – Reliability and construct validity. Psychology, 2, 283–290. http://doi.org/bj6t9b

Ivarsson, B., & Malm, U. (2007). Self-reported consumer satisfaction in mental health services: Validation of a self-rating version of the UKU-Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 61, 194–200. http://doi.org/cb67f3

Ivarsson, B., Malm, U., Lindström, L., & Norlander, T. (2010). The self-assessment Global Quality of Life Scale: Reliability and construct validity. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 14, 287–297. http://doi.org/chgnt6

Mahon, P. Y. (1996). An analysis of the concept ‘patient satisfaction’ as it relates to contemporary nursing care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24, 1241–1248. http://doi.org/fbh7hj

Nordén, T., Ivarsson, B., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2011). Gender and treatment comparisons in a cohort of patients with psychiatric diagnoses. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 39, 1073–1086. http://doi.org/d8rqqb

Nordén, T., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2012). Resource Group Assertive Community Treatment (RACT) as a tool of empowerment for clients with severe mental illness: A meta-analysis. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8, 144–151. http://doi.org/f24vwm

Norlander, T., Ernestad, E., Moradiani, Z., & Nordén, T. (2015). Perceived feeling of security: A candidate for assessing remission in borderline patients? Open Psychology Journal, 8, 146–152. http://doi.org/9v9

Pedersen, G., Hagtvet, K. A., & Karterud, S. (2007). Generalizability studies of the Global Assessment of Functioning–Split version. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48, 88–94. http://doi.org/bbp9rg

Siponen, U., & Välimäki, M. (2003). Patients’ satisfaction with outpatient psychiatric care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10, 129–135. http://doi.org/ctw7kg

World Medical Association. (2008). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Retrieved from http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf

Ahlfors, U. G., Lewander, T., Lindström, E., Malt, U. F., Lublin, H., & Malm, U. (2001). Assessment of patient satisfaction with psychiatric care. Development and clinical evaluation of a brief consumer satisfaction scale (UKU-ConSat). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 55, 71–90. http://doi.org/bwk6pz

American Psychiatric Association. (2002). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.: DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: Author.

Andersson, J., Ivarsson, B., Tungström, S., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2014). The Clinical Strategies Implementation Scale revised (CSI-R). Fidelity assessment of Resource Group Assertive Community Treatment. Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 3, 36–41. http://doi.org/9th

Angantyr, K., Rimner, A., Nordén, T., & Norlander, T. (2015). Primary care behavioral health model: Perspectives of outcome, client satisfaction, and gender. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 43, 287–301. http://doi.org/9tj

Erdner, L., & Ivarsson, B. (2001). The Quality Star – A tool for regular outcome monitoring [Monograph]. In M. London (Ed.), ENTER conference monographs, London 2000, Paris 2001 (pp. 65–69). Cambridge: Print Out.

Gemensamma Genomförandegruppen. (2013). Rapport för år 2012. Förslag till fortsatta aktiviteter år 2013 [Report from 2012. Suggestions for future activities for the year 2013]. Kungälv: Kvalitetsstjärnan. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/27SSvxH

Helldin, L., Kane, J., Karilampi, U., Norlander, T., & Archer, T. (2008). Experience of quality of life and attitude to care and treatment in patients with chronic schizophrenia: Role of cross-sectional remission. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 12, 97–104. http://doi.org/d4h8f8

Howard, P. B., Rayens, M. K., El-Mallakh, P., & Clark J. J. (2007). Predictors of satisfaction among adult recipients of medicaid mental health services. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 21, 257–269. http://doi.org/bh3bv7

Ingvarsson, T., Nordén, T., & Norlander, T. (2014). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: A case study on experiences of healthy behaviors by clients in psychiatric care. Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 3, 390–402. http://doi.org/9v6

Ivarsson, B. (2011). Tools for outcome-informed management of mental illness: Psychometric properties of instruments of the Swedish clinical multicenter Quality Star cohort (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Karlstad University, Sweden.

Ivarsson, B., Erdner, L., & Malm, U. (2006, June). The Quality Star—An algorithm for the evaluation of mental health services. Presentation for ENMESH conference, Lund, Sweden (Vol. 10). Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1HVd1UU

Ivarsson, B., Lindström, L., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2011a). Consumer satisfaction, quality of life and distress with regard to social function and gender in severe mental illness. Open Journal of Psychiatry, 1, 88–97. http://doi.org/ffqkt9

Ivarsson, B., Lindström, L., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2011b). The self-assessment of Perceived Global Distress Scale – Reliability and construct validity. Psychology, 2, 283–290. http://doi.org/bj6t9b

Ivarsson, B., & Malm, U. (2007). Self-reported consumer satisfaction in mental health services: Validation of a self-rating version of the UKU-Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 61, 194–200. http://doi.org/cb67f3

Ivarsson, B., Malm, U., Lindström, L., & Norlander, T. (2010). The self-assessment Global Quality of Life Scale: Reliability and construct validity. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 14, 287–297. http://doi.org/chgnt6

Mahon, P. Y. (1996). An analysis of the concept ‘patient satisfaction’ as it relates to contemporary nursing care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24, 1241–1248. http://doi.org/fbh7hj

Nordén, T., Ivarsson, B., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2011). Gender and treatment comparisons in a cohort of patients with psychiatric diagnoses. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 39, 1073–1086. http://doi.org/d8rqqb

Nordén, T., Malm, U., & Norlander, T. (2012). Resource Group Assertive Community Treatment (RACT) as a tool of empowerment for clients with severe mental illness: A meta-analysis. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8, 144–151. http://doi.org/f24vwm

Norlander, T., Ernestad, E., Moradiani, Z., & Nordén, T. (2015). Perceived feeling of security: A candidate for assessing remission in borderline patients? Open Psychology Journal, 8, 146–152. http://doi.org/9v9

Pedersen, G., Hagtvet, K. A., & Karterud, S. (2007). Generalizability studies of the Global Assessment of Functioning–Split version. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48, 88–94. http://doi.org/bbp9rg

Siponen, U., & Välimäki, M. (2003). Patients’ satisfaction with outpatient psychiatric care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10, 129–135. http://doi.org/ctw7kg

World Medical Association. (2008). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Retrieved from http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/17c.pdf

Table 1. Items for Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale – Revised (ConSat–R) With Anchor Points (Low, High)

Table 2. Means and Standard Deviations in Raw Scores for Items

Table 3. Correlations (Spearman’s rho) in Regard to Items and Total Scores

The authors express their gratitude to all the clients and local researchers who contributed to this study. Locations with participants from both psychiatry and the social services were Hä

rryda

Hä

ssleholm

Kristianstad

Mö

lndal

Partille

Ö

rebro

locations with participants from only psychiatry were Leksand

Lindesberg

Ljungby

and locations with participants from only the social services were Ljusnarsberg and Skö

vde.

The following individuals were part of the working group that constructed the revised version of the ConSat

Ingrid Andersson

Jonny Andersson

Ewa Axelsson

Per Bergman

Birgit Bengtsson

Kerstin Evelius

Bo Ivarsson

Jill Larsen

Ulf Malm

Christel Norrud

Camilla Palmer

Margareta Runhede

Sö

ren Sä

terhagen

and Stefan Tungströ

m.

Torsten Norlander, Center for Research and Development, Evidens University College, Packhusplatsen 2, SE-411 13 Göteborg, Sweden. Email: [email protected] or [email protected]