College students' cheating behaviors

Main Article Content

I explored the reasons given by college students for cheating during scholastic examinations. The participants were 26 students from Marmara University in Turkey. It was observed that most of the students identified cheating as taking reminder notes into an examination, getting help during the examination, or theft of knowledge. The tendency to cheat in a variety of ways was found to be high, particularly with regard to the preparation of cheating materials before the examination. While some students justified helping friends they are close to or who they observe as having difficulties, others considered it immoral and refused to be involved in the activity of cheating. Lastly, students generally did not feel regret if the examination consisted of questions where the answers depend solely on memorization or if there was a common belief that the lesson would have no use for their future career or lives.

The institutional concept of cheating or plagiarism is considered a form of academic dishonesty (Godden, 2001; McCabe & Pavela, 2000). The Turkish Language Association (1988) defined cheating as “secretly benefiting by preparing correct answers to examinations in advance from a source or obtaining them directly from a person during the examination.” Cheating, therefore, means accessing unauthorized sources during examinations or academic homework, or coercing others to prepare work for you, instead of answering the questions yourself. It can also involve planning to secretly access sources during the examination or helping others to cheat (Semerci & Sağlam, 2005; Tan, 2001). Plagiarism, as defined in the Grand Dictionary of Turkish Language (Turkish Language Association, 1988), is the partial or total appropriation of another individual’s work, theft of words and script, or literal theft. Kibler, Nuss, Peterson, and Pavela (1988) defined academic dishonesty as forms of cheating and plagiarism that involve students giving or receiving unauthorized assistance in an academic exercise or receiving credit for work that is not their own. Pavela (1978, p.78) provided the following definitions of the various types of academic dishonesty: Cheating is “intentionally using or attempting to use unauthorized materials, information, or study aids in an academic exercise.” Fabrication is “the intentional and unauthorized falsification or invention of any information or citation in any academic exercise.” Facilitating academic dishonesty is “intentionally or knowingly helping or attempting to help another violate a provision of the institutional code of academic integrity.” Plagiarism is “the deliberate adoption or reproduction of ideas, words, or statements of another person as one’s own without acknowledgement.”

In 1964 Bill Bowers conducted the first studies on academic cheating, revealing that 75% of respondents had cheated at least once in their lives (as cited in Blachnio & Weremko, 2011). Since that time the tendency towards cheating – which is, in essence, dishonesty and, therefore, a serious problem – has increased in many countries, including Turkey (Blachnio & Weremko, 2011; Bozdoğan & Öztürk, 2008; Diekhoff, LaBeff, Shinohara, & Yasukawa, 1999; Grimes, 2004; Lin & Wen, 2007; Lupton & Chapman, 2002; Paldy, 1996). Cheating can be viewed as both a moral and a social decision. Thus, a student’s attitude about whether he/she personally believes cheating to be right or wrong is considered to be of great importance (O’Rourke et al., 2010). Researchers have noted that the tendency towards cheating increases during the later years of university study (Bekaroğlu, 2002; Carpenter, Harding, Finelli, Montgomery, & Passow, 2006; Paldy, 1996; Roig & Caso, 2005; Semerci, 2004; Semerci & Sağlam, 2005). Cheating is a conscious behavior that changes over time throughout the period of learning and acquisition in educational science faculties. In light of this, lecturers believe that a students’ tendency to cheat will result in a decreasing quality of work in their future professional lives.

By investigating university students who are frequently involved in cheating, my aim in this study was to identify the behaviors students utilize to cheat and to find out why they do so rather than relying on their own ideas or knowledge.

Method

Participants

During the 2012–2013 academic year, 26 students from the University of Marmara volunteered to participate in this study. Of these students, 8 were from the Music Teaching Division, 3 from the French Language Teaching division, 6 from the Art Teaching division, 6 from the Turkish Language Teaching division, and 3 from the German Language Teaching division.

Data Collection

Data were gathered and derived from the students using semistructured interviews, a qualitative research technique, logged using voice recording devices. Results were gathered by two measurement and evaluation specialists and one Turkish language specialist, all of whom provided input into the necessary adjustments and revisions to the interview process. In order to determine if the questions included were comprehensive, I administered the interview to four students. The interview questions were suitable and we continued with this version of the interview form.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to analyze the data by summarizing and commenting on each data point according to predetermined themes (Yıldırım & Şimşek, 2008). Data were digitized and are presented in tables here.

Results and Discussion

On the semi-structured interview forms students were first asked how they would describe cheating. Responses are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Students’ Descriptions of Types of Cheating

In response to the questions “What is your idea of cheating?” and “How do you identify cheating?”, almost one fourth of participants said that they keep reminder notes and more than 10% solicited help from a person sitting nearby or from external reminder paper when they realized they were incapable of answering for themselves. Kaymakcan (2002) found that the number of students who claim that cheating is a theft of knowledge was 6.4%, which is lower than the figure of 10.26% gained in this study. This does not support Kaymakcan’s research findings. Most of the students in this study considered cheating as a simple reminder and an innocent way to get help, and tended to describe it in an innocuous way.

When students take an examination, they may encounter other students who are cheating. More than three quarters of the participants in this study had cheated from other students’ examination papers. According to the data I obtained, higher levels of interest in looking at the examination papers of others who are cheating had a positive relationship with increased tendency to cheat.

Table 2. Reasons for Using Others’ Papers to Cheat During the Examination

As can be seen in Table 2, students cheat when they do not know the answer to the question, if they are unsure of which of two plausible answers is correct, or if they feel the need to correct or control what they have previously written. Feeling the need to cheat by looking at others’ examination papers during the examination is primarily explained by either not knowing or being unable to answer the question, or vacillating between two similar answers to the question.

When asked “Do you cheat on every examination?” over 65% of participants responded affirmatively. This finding is similar to that of Kaymakcan (2002) who found that 63.5% of students had a tendency towards cheating with varying frequency.

Table 3. Reasons for Cheating on an Examination

As can be seen in Table 3, almost half of students cheated when examinations were based on memorization; more than 10% cheated when teachers presented the lesson as more difficult than it actually is; and almost 10% cheated when teachers overlooked cheating during the examination, if lessons were taught by a teacher from a different branch of education, or when it was considered that a teacher could not teach the lesson effectively. Carpenter et al. (2006) found that perceptions of a teacher being incapable of effectively presenting a lecture caused an increase in the rate of cheating during examinations.

When students were asked “Before entering the examination room, do students really prepare cheating materials?” more than half of the students admitted to doing so. Most stated that they prepare cheating materials for only the examination itself. Over 65% of students attempted to cheat, close to 12% of whom claimed not to have made any advance preparation.

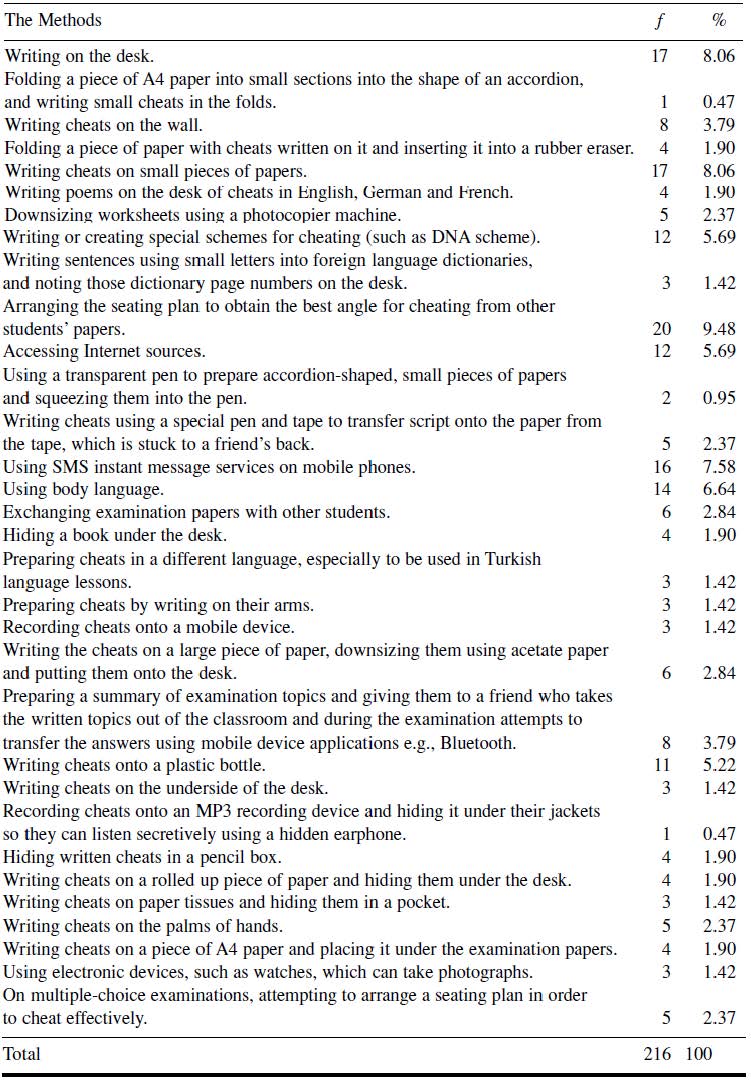

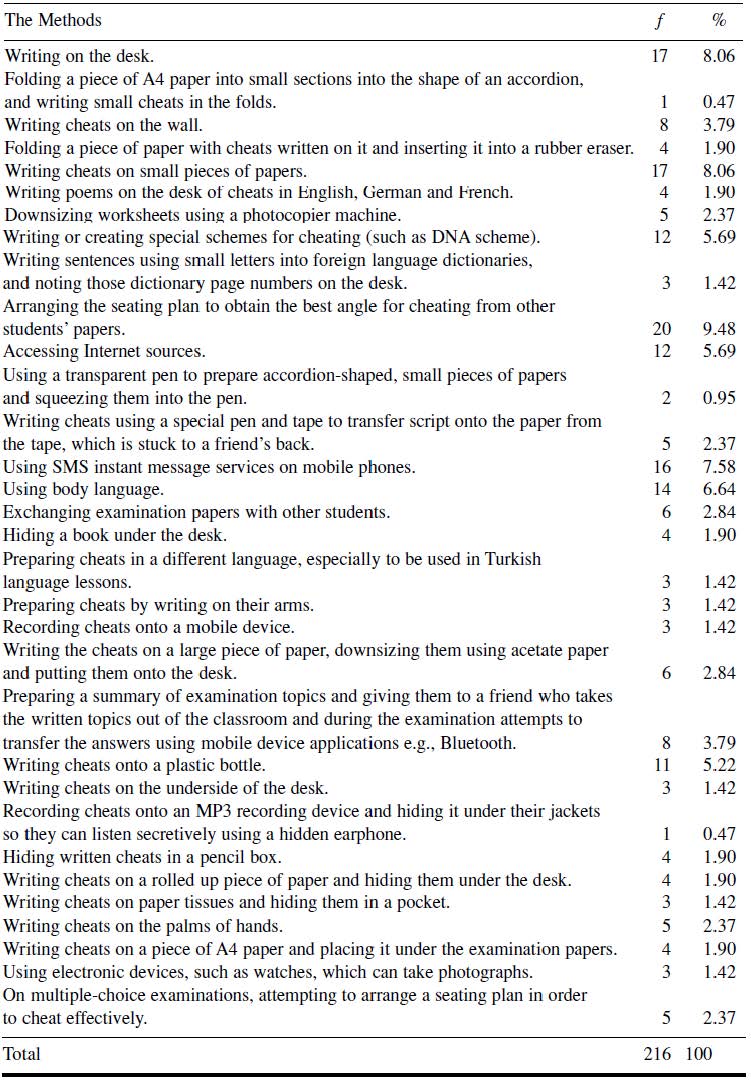

Table 4. Methods of Preparing Cheating Materials

As can be seen in Table 4, students attempted to arrange seating positions in order to gain a vantage point to cheat from their friends, wrote notes on the desk, prepared small cheating notepads in advance, used mobile phone SMS instant messaging services, and used body language and signs to cheat. These research results are similar to those of Kaymakcan (2002) and Eraslan (2011), whose participants admitted that they tend to write on desks, cheat from a friend’s examination papers, and expose his/her examination paper to others during the examination. Conversely, the least used methods for cheating were using a transparent pen, using a piece of A4 paper folded in half like an accordion, and recording the examination information into a mobile recording MP3 device and attempting to listen through headphones hidden in a jacket.

Over three quarters of students who attempted to cheat planned to do so in advance.

Table 5. Techniques to Aid Cheating Which are Prepared Before the Examination

As can be seen in Table 5, the most commonly used cheating technique was sitting behind a friend who had studied well in advance for the examination. Sitting beside or behind a trusted friend, sitting by or near the classroom wall or preferring to sit by a window, and sitting near students who had worked hard, in order to copy from them, in multiple-choice examinations were also popular methods. I found that it is common practice to plan and organize the cheating technique before the examination. According to my findings, students who received help cheating on examinations are the same ones who help their friends to cheat, while those who did not want help to cheat are also the ones who refused to help others to cheat.

Table 6. Reasons Given for Helping Others Cheat

As can be seen in Table 6, reasons for cheating were found to include the intention to help someone during the examination, to initiate a personal relationship, to help someone who is in trouble, and to help a friend who has not studied for the examination. The least common reason for helping others cheat was when the student’s own examination went well and then they helped others cheat. Based on results from this study, the most common reason why a student would help another cheat during an examination was to initiate a personal friendship.

Table 7. Reasons Given For Not Helping Others Cheat on an Examination

As can be seen in Table 7, the most common reason given for not helping others cheat during the examination was the belief that helping someone to cheat is immoral. The least common reason was that the students did not want to help if others had not prepared by themselves or had not studied for the examination.

Half of those who cheated stated that they felt disturbed or ashamed. Of note, over half of the students attempted to cheat on every examination despite feeling ashamed or disturbed.

Table 8. Reason for Experiencing a Guilty Conscience During an Examination

As can be seen in Table 8, almost half of the students stated that they had a guilty conscience when they cheated on an examination because they think it is unfair to exploit another person’s rights. One quarter of students felt guilty because they liked the teacher overseeing the examination.

Table 9. Reasons for Not Experiencing a Guilty Conscience When Attempting to Cheat During an Examination

As can be seen in Table 9, the most prevalent reason for not feeling guilt for cheating was when an examination depended on memorization. Students also did not feel guilty for cheating if they perceived that the information from the examination would not be needed in their future professions. It can be said that when examinations are designed to test nonfunctional information and skills, students are less likely to refrain from cheating.

Conclusion

Recommendation

In order to reduce the rate of cheating during examinations, lecturers should prepare relevant questions and ensure correct answers do not depend solely on memorization. Also, with regard to multiple-choice examinations, seating arrangements should be allocated by the lecturer rather than being influenced by the students. In order to prevent cheating preparation in the classroom, students should not be allowed in the classroom before the examination begins. Enforcing heavier penalties for probable cheating is also crucial for decreasing the rate of cheating. The prospective teachers who are studying at the Faculty of Education, in anticipation of future work in classrooms should be role models for their own students in future years after graduation. For this reason, the cheating behaviors of college students requires further attention from researchers.

References

Bekaroğlu, Ö. (2002). Scientific dishonesty in the world and in Turkey [In Turkish]. Tuba Bulletin, Diary, 22, 12-13.

Blachnio, A., & Weremko, M. (2011). Academic cheating is contagious: The influence of the presence of others on honesty. A study report. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 1, 14-19.

Bozdoğan, A. E., & Öztürk, Ç. (2008). Why do teacher’ candidates cheat? Elementary Education Online, 7, 141-149.

Carpenter, D. D., Harding, T. S., Finelli, C. J., Montgomery, S. M., & Passow, H. J. (2006). Engineering students’ perceptions of and attitudes towards cheating. Journal of Engineering Education, 95, 181-194. http://doi.org/q5j

Godden, D. (2001). Plagiarism: A brief survey and report written for Education 750: Principles and Practice of University Teaching. Retrieved from: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/237445892_Plagiarism_A_Brief_Survey_Report_Written_for_ Education_750_Principles_and_Practice_of_University_Teaching

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Shinohara, K., & Yasukawa, H. (1999). College cheating in Japan and the United States. Research in Higher Education, 40, 343-353. http://doi.org/fvbk7g

Grimes, P. W. (2004). Dishonesty in academics and business: A cross-cultural evaluation of student attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 49, 273-290. http://doi.org/dpf297

Eraslan, A. (2011). Prospective mathematics teachers and cheating: It is a lie if I say I have never cheated! [In Turkish]. Education and Science, 36, 52-64.

Kaymakcan, R. (2002). Theology faculty students’ attitudes about cheating [In Turkish]. Sakarya University, Journal of Theology Faculty, 5, 121-138.

Kibler, W., Nuss, E., Peterson, B., & Pavela, G. (1988). Academic integrity and student development: Legal issues, policy perspectives. Asheville, NC: College Administration.

Lin, C.-H. S., & Wen, L.-Y. M. (2007). Academic dishonesty in higher education: A nationwide study in Taiwan. Higher Education, 54, 85-97. http://doi.org/dx25mp

Lupton, R. A., & Chapman, K. J. (2002). Russian and American college students’ attitudes, perceptions, and tendencies towards cheating. Educational Research, 44, 17-27. http://doi.org/bgbwxn

McCabe, D., & Pavela, G. (2000). Some good news about academic integrity. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 32, 32-38. http://doi.org/cn2tct

Paldy, L. G. (1996). The problem that won’t go away: Addressing the causes of cheating. Journal of College Science Teaching, 26, 4-6.

Pavela, G. (1978). Judicial review of academic decisionmaking after Horowitz. NOLPE School Law Journal, 55, 55-75.

O’Rourke, J., Barnes, J., Deaton, A., Fulks, K., Ryan, K., & Rettinger, D. (2010). Imitation is the sincerest form of cheating: The influence of direct knowledge and attitudes on academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 20, 47-64. http://doi.org/cw3zvj

Roig, M., & Caso, M. (2005). Lying and cheating: Fraudulent excuse making, cheating, and plagiarism. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 139, 485-494. http://doi.org/b76xct

Semerci, C. (2004). Medical faculty students’ attitudes and opinions towards cheating [In Turkish]. Firat University Journal of Health Sciences, 18, 139-146.

Semerci, C., & Sağlam, Z. (2005). Attitudes and ideas towards cheating of policeman candidates in exams [In Turkish]. Firat University Journal of Social Science, 15, 163-177.

Tan, S. (2001). Prevention of cheating in exams [In Turkish]. Education and Science, 26, 32-40.

Turkish Language Association. (1988). Official dictionary of the Turkish language [In Turkish]. Istanbul: Beyand.

Yıldırım, A., & Şimşek, H. (2008). Qualitative research methods in social sciences (8th ed.) [In Turkish]. Ankara: Seckin.

Bekaroğlu, Ö. (2002). Scientific dishonesty in the world and in Turkey [In Turkish]. Tuba Bulletin, Diary, 22, 12-13.

Blachnio, A., & Weremko, M. (2011). Academic cheating is contagious: The influence of the presence of others on honesty. A study report. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 1, 14-19.

Bozdoğan, A. E., & Öztürk, Ç. (2008). Why do teacher’ candidates cheat? Elementary Education Online, 7, 141-149.

Carpenter, D. D., Harding, T. S., Finelli, C. J., Montgomery, S. M., & Passow, H. J. (2006). Engineering students’ perceptions of and attitudes towards cheating. Journal of Engineering Education, 95, 181-194. http://doi.org/q5j

Godden, D. (2001). Plagiarism: A brief survey and report written for Education 750: Principles and Practice of University Teaching. Retrieved from: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/237445892_Plagiarism_A_Brief_Survey_Report_Written_for_ Education_750_Principles_and_Practice_of_University_Teaching

Diekhoff, G. M., LaBeff, E. E., Shinohara, K., & Yasukawa, H. (1999). College cheating in Japan and the United States. Research in Higher Education, 40, 343-353. http://doi.org/fvbk7g

Grimes, P. W. (2004). Dishonesty in academics and business: A cross-cultural evaluation of student attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 49, 273-290. http://doi.org/dpf297

Eraslan, A. (2011). Prospective mathematics teachers and cheating: It is a lie if I say I have never cheated! [In Turkish]. Education and Science, 36, 52-64.

Kaymakcan, R. (2002). Theology faculty students’ attitudes about cheating [In Turkish]. Sakarya University, Journal of Theology Faculty, 5, 121-138.

Kibler, W., Nuss, E., Peterson, B., & Pavela, G. (1988). Academic integrity and student development: Legal issues, policy perspectives. Asheville, NC: College Administration.

Lin, C.-H. S., & Wen, L.-Y. M. (2007). Academic dishonesty in higher education: A nationwide study in Taiwan. Higher Education, 54, 85-97. http://doi.org/dx25mp

Lupton, R. A., & Chapman, K. J. (2002). Russian and American college students’ attitudes, perceptions, and tendencies towards cheating. Educational Research, 44, 17-27. http://doi.org/bgbwxn

McCabe, D., & Pavela, G. (2000). Some good news about academic integrity. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 32, 32-38. http://doi.org/cn2tct

Paldy, L. G. (1996). The problem that won’t go away: Addressing the causes of cheating. Journal of College Science Teaching, 26, 4-6.

Pavela, G. (1978). Judicial review of academic decisionmaking after Horowitz. NOLPE School Law Journal, 55, 55-75.

O’Rourke, J., Barnes, J., Deaton, A., Fulks, K., Ryan, K., & Rettinger, D. (2010). Imitation is the sincerest form of cheating: The influence of direct knowledge and attitudes on academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 20, 47-64. http://doi.org/cw3zvj

Roig, M., & Caso, M. (2005). Lying and cheating: Fraudulent excuse making, cheating, and plagiarism. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 139, 485-494. http://doi.org/b76xct

Semerci, C. (2004). Medical faculty students’ attitudes and opinions towards cheating [In Turkish]. Firat University Journal of Health Sciences, 18, 139-146.

Semerci, C., & Sağlam, Z. (2005). Attitudes and ideas towards cheating of policeman candidates in exams [In Turkish]. Firat University Journal of Social Science, 15, 163-177.

Tan, S. (2001). Prevention of cheating in exams [In Turkish]. Education and Science, 26, 32-40.

Turkish Language Association. (1988). Official dictionary of the Turkish language [In Turkish]. Istanbul: Beyand.

Yıldırım, A., & Şimşek, H. (2008). Qualitative research methods in social sciences (8th ed.) [In Turkish]. Ankara: Seckin.

Table 1. Students’ Descriptions of Types of Cheating

Table 2. Reasons for Using Others’ Papers to Cheat During the Examination

Table 3. Reasons for Cheating on an Examination

Table 4. Methods of Preparing Cheating Materials

Table 5. Techniques to Aid Cheating Which are Prepared Before the Examination

Table 6. Reasons Given for Helping Others Cheat

Table 7. Reasons Given For Not Helping Others Cheat on an Examination

Table 8. Reason for Experiencing a Guilty Conscience During an Examination

Table 9. Reasons for Not Experiencing a Guilty Conscience When Attempting to Cheat During an Examination